The Changing Science of Just-About-Birds and Not-Quite-Birds

When people say that scientists are always changing their minds, it’s usually meant as a slight. How can anyone trust conclusions that are so prone to revision? But the fluctuating nature of science is a feature not a bug. It means that our knowledge of the world is constantly being updated in the face of new evidence.

For example, scientists from the University of Bristol recently showed that the evolutionary relationships between different dinosaurs are continuously changing in the light of new fossils. It’s a bit of an etch-a-sketch science—no sooner are family trees drawn before they’re re-drawn again. Even well-known transitions are prone to big shake-ups.

Consider the origin of birds. There is now overwhelming evidence that birds evolved from small predatory dinosaurs. Hundreds of stunning fossils illustrate the transitions from dino-fuzz to flight feathers and from grasping arms to flapping wings. The avialans (all birds, living and extinct) fit within a group of dinosaurs called the Paraves, which also includes dromaeosaurids (sickle-clawed predators like Velociraptor and Deinonychus) and troodontids (large-brained predators like Troodon).

But which of these creatures were the first birds, and which specific group of paravians were their closest relatives? That’s still the subject of heavy debate.

The famous Archaeopteryx, with its winged arms, clawed hands, toothed jaws, and long bony tail, was one of the first fossils to suggest a link between birds and other dinosaurs. Since its discovery in 1861, it has been widely heralded as one of the earliest birds (avialans). But two years ago, Chinese palaeontologist Xing Xu cast its pivotal position into doubt.

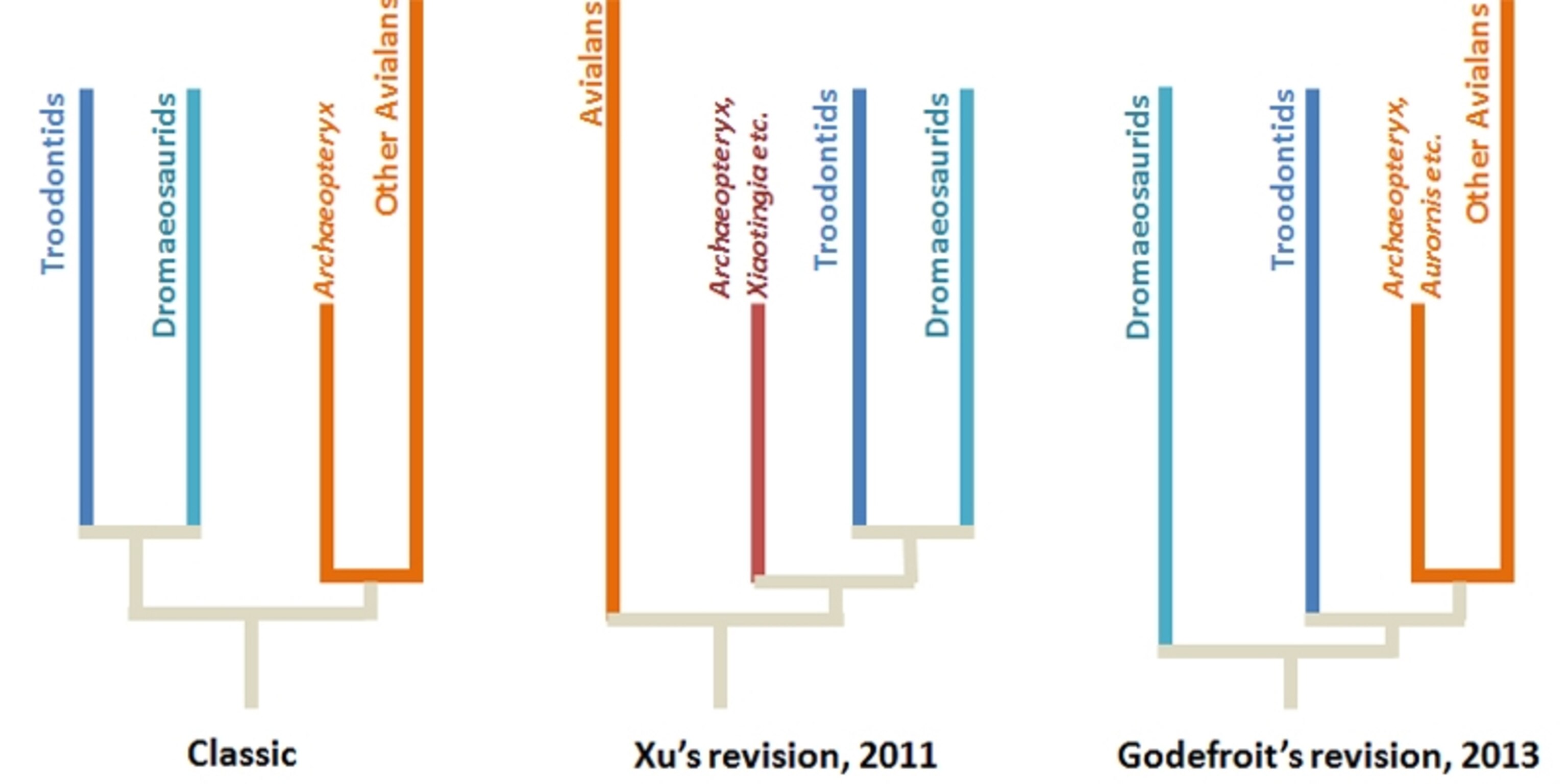

Xu, who has discovered more feathered dinosaurs than anyone else, had just found a new species called Xiaotingia. By comparing this creature with Archaeopteryx and other related species, Xu created a family tree that put Archaeopteryx outside the avialans (see diagram below). Instead, it sat next to the dromaeosaurids and troodontids, together with relatives like Xiaotingia and Anchiornis. The first bird was no bird at all.

If Xu was right, the implications would have been profound. For a start, Archaeopteryx clearly had wings with what looked like flight feathers. If it was a bird, then flapping flight probably evolved once in the lineage leading to modern birds. If it wasn’t a bird, then flight evolved twice—once in Archaeopteryx’s group and again in modern birds. (Or, alternatively, the dromaeosaurids and troodontids all lost the ability by reducing their wings.)

But was Xu right? He himself said that his revised family tree only had “tentative statistical support”. Later in 2011, Mike Lee from the South Australian Museum showed that a different tree, built with different methods, reinstated Archaeopteryx as a bird.

Pascal Godefroit from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science entered the debate this January, with a new dinosaur called Eosinopteryx. There were many echoes of Xu’s study: Godefroit also placed the paravians on a family tree, also concluded that Archaeopteryx was no bird, and also said that the result was statistically weak.

Now, his team is back with yet another maybe-a-bird fossil and yet another revised paravian family tree… and this one contradicts his own earlier conclusions (see diagram below). It once again restores Archaeopteryx as an early bird, while settling related species on different perches.

The fossil in question is called Aurornis xui, and it lived 160 million years ago in northeastern China. Aurornis is Latin for “dawn bird” but the animal’s species name honours Xing Xu. For Godefroit, the decision was an easy one. “Xu has completely revolutionised our vision of dinosaur biology and evolution,” he says. “Although he is still very young and extremely modest, he is probably the most important living vertebrate palaeontologist.” Modest is right—in typical form, Xu says that he’s treating the “great honour” as recognition of the contributions that Chinese palaeontologists have made as a group.

Aurornis is beautifully preserved and has much the same features as Xiaotingia, Anchiornis, Eosinopteryx, and Archaeopteryx. Godefroit’s team believe that it’s a distinct species based on a few characteristic features, although Steven Brusatte from the University of Edinburgh says, “I can’t shake a nagging suspicion that some of these may be juveniles and adults of the same [species]. The only way to know for sure will be to check the internal structures of the specimens’ bones.

Regardless, it’s clear that these animals all lived at roughly the same time, in the same place—the Tiaojishan Formation in northeastern China. This treasure trove of fossils was once home to an entire flock of not-quite-birds and just-about-birds that all and looked rather similar and lived near each other. It’s no wonder that their evolutionary relationships are difficult to entangle.

Godefroit’s team didn’t want to create another weak family tree, so they started from scratch. Italian scientist Andrea Cau scoured the literature and compiled data on 101 species of dinosaurs and birds, scoring each skeleton according to almost 1,000 characteristics. “It’s very impressive,” says Lee. “They considered more than twice as much anatomical information as even the best previous analyses.”

The results put Archaeopteryx back in its traditional roost as an avialan, but no longer as the earliest one. That honour goes to Aurornis itself. It’s now the most primitive bird, followed by Anchiornis, Archaeopteryx and Xiaotingia in that order. (Eosinopteryx, perhaps surprisingly, emerges as a very early paravian that preceded the groups I’ve already mentioned.)

“If Aurornis is the most primitive bird, then it is a huge discovery,” says Brusatte, “but I am not convinced that this paper resolves the early history of birds.” Xu agrees. He says the results deserved to be taken seriously, but adds that several parts of the family tree are inconsistent with earlier work. He’s not just talking about Archaeopteryx. For example, among the other dinosaurs, the troodontids emerge as the group that’s closest to the birds. And the biggest surprise isn’t even mentioned in the paper! Here it is:

Balaur is a Romanian dinosaurBalaur is a Romanian dinosaur that was discovered in 2010. Its discoverers (including Brusatte) concluded that it was a close relative of Velociraptor; the two dinosaurs look very similar, although Balaur is stockier of build and has two sickle-claws on each foot rather than one. But Godefroit’s family tree has it perching firmly within the birds! It’s not alone; other supposedly non-bird species like Rahonavis and Shenzouraptor have been similarly displaced.

That’s a huge shake-up, and puzzling one given these animals’ appearances. “I am suspicious,” says Brusatte. “It is certainly possible that Balaur is a bird but I would be surprised if this is the case.” Godefroit says, “It was also a big surprise for us!” One of their team—Gareth Dyke—even went to check the original specimen to make sure that they hadn’t made any obvious mistakes.

Godefroit plans to publish a separate paper to address this discrepancy. For the moment, it raises some scepticism that has spread to other parts of the tree. “It suggests that some other results, such as the status of Archaeopteryx, Anchiornis, Aurornis and Xiaotingia need further evaluation,” says Xu.

“I am confident that specimens from the Tiaojishan Formation will end up solving this debate somewhere down the line,” says Brusatte, “and I predict that something that all workers agree is a true bird will eventually be found there. Maybe Aurornis is that bird; maybe not.”

As more evidence comes in, the etch-a-sketch will almost certainly shake again, and new versions of the paravian family tree will emerge. “I hope so,” says Godefroit. “Otherwise, palaeontology will become as dull as dishwater!”

Reference: Godefroit, Cau, Yu, Escuillie, Wenhao & Dyke. 2013. A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds. Nature http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature1216

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?