The Unlikely Story of the Map That Helped Create Our Nation

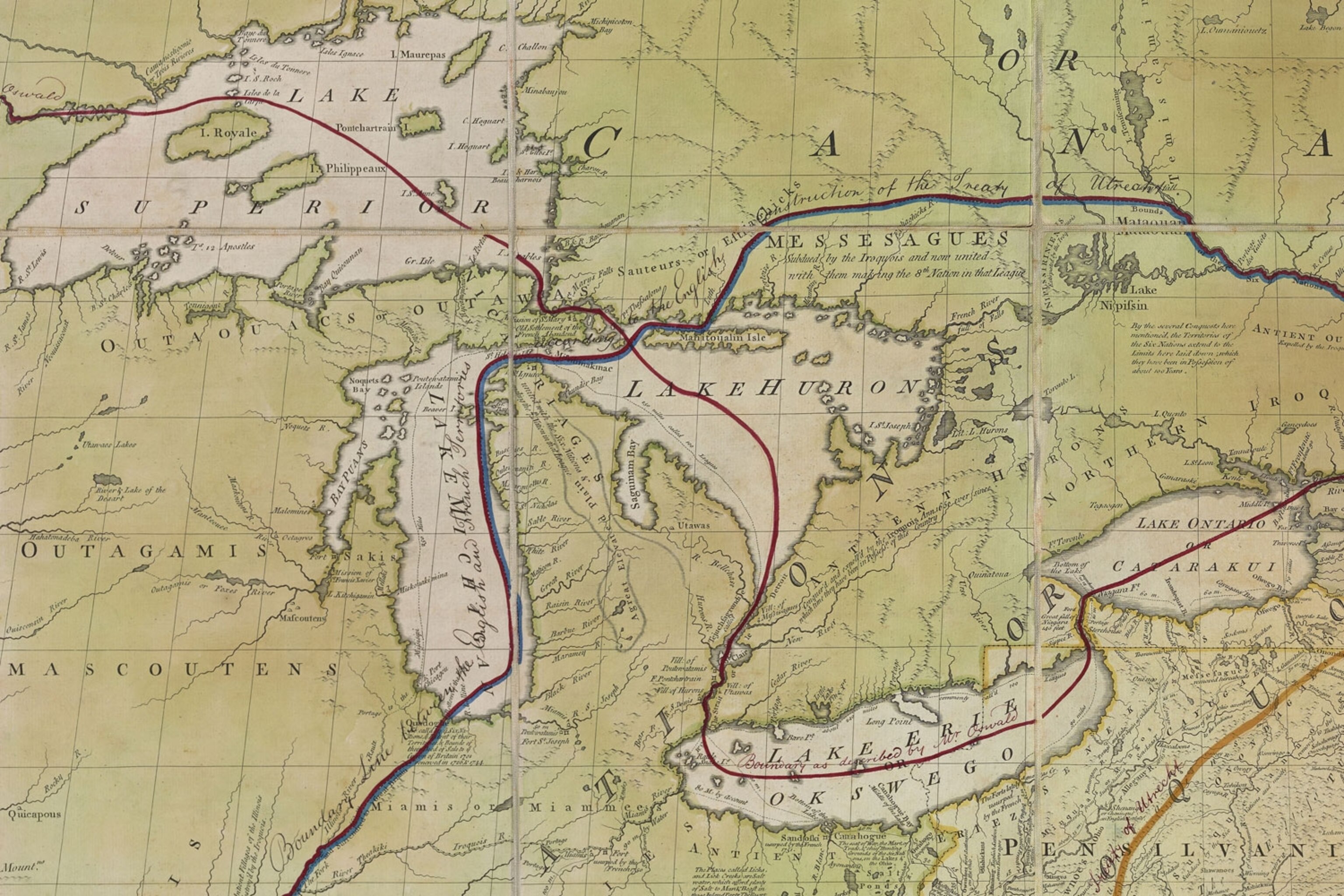

It’s arguably the most important map in our country’s history. After the Revolutionary War, British and American representatives met in Paris to negotiate the boundaries of a new nation: the United States of America. Both sides had a version of the same map, marked up to indicate where they thought the lines should be drawn.

“The diplomats literally debated the boundaries of the future United States while pointing at this map,” says Matthew Edney, a historian of cartography at the University of Southern Maine. Although the 1783 Treaty of Paris contains no maps or illustrations, its written descriptions of boundaries are based on the marked-up maps of the negotiators, Edney says.

The map used as a starting point by both sides was created by a Virginia-born doctor named John Mitchell and published for the first time in 1755. Mitchell’s map is well-known among historians and map librarians, but less so among the general public. That’s too bad because it has a fascinating story.

If Mitchell had lived long enough to see how his map came to be used, he might have been appalled. Although the map played a role in loosening Britain’s imperial grip on North America, its original purpose was just the opposite.

John Mitchell was born in 1711 to a family of relatively wealthy tobacco farmers. He studied medicine abroad, at the University of Edinburgh, then returned to his native Virginia to practice. He and his wife lived near the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay, which would have been a swampy, steamy, mosquito-ridden place in those days, Edney says. The couple fell into poor health, and in 1746 they retreated to the cooler climes of Britain to recuperate.

In London, Mitchell began mingling in high society, apparently aided by his knowledge of botany, a hot topic among learned men of his day. “He’s hobnobbing with aristocrats who were really into gardening,” Edney says. “And he comes into contact with a lot of politicians who were also demon gardeners.”

One introduction led to another, and eventually the Earl of Halifax took notice of Mitchell. Halifax presided over the Board of Trade and Plantations, which oversaw colonial affairs. At the time Halifax was trying to rally the British government to defend the North American territories against incursions by the French. Halifax saw Mitchell as a native expert on North America and commissioned him to make a map to help his cause.

Mitchell had no formal training in cartography or geography, and there’s nothing to suggest he had any previous interest in those topics, Edney says. Yet he created what may well have been the best map of North America available in the late 18th century, drawing upon the Board’s archives in London, as well as surveys and maps Halifax ordered from the colonial governors.

Mitchell’s map took a decidedly British view of who owned what on the continent. His boundary lines, and small notes he scattered across the map, favored British claims over those made by the Spanish and French.

In Florida, for example, Mitchell drew a southern boundary line well inside the territory claimed by Spain. In Alabama, there’s a small note that reads “A Spanish fort built in 1719 & said to be soon after abandoned,” an apparent effort to diminish any Spanish claims to the land.

Others began making derivatives of Mitchell’s map that were even more politically pointed. “In the 1750s there was a whole series of what’s called Anti-Gallican societies basically saying ‘We need to boycott the French,’” Edney says. The map below was made by one of these groups. It cedes even less land to the French than Mitchell’s map does, and it highlights French forts built too close for comfort around British territory.

The title of that map is rife with pompous indignation:

A New and accurate Map of the English Empire in North America Representing their Rightful claim as confirmed by Charters and the formal Surrender of their Indian Friends, Likewise the Encroachments of the French with several Forts they have unjustly erected therein.

The Anti-Gallican maps based on Mitchell’s map helped stir up anti-French sentiment in Britain, Edney says. “In that sense, Mitchell’s map was really crucial,” he says. “It’s one of the very first maps we can actually document as having a political impact.”

That impact was huge: By swaying public (and political) opinion toward standing up to the French instead of appeasing them, the map helped precipitate the French and Indian War. That war, in turn, created the conditions that led to the Declaration of Independence 240 years ago today. Fighting the French blew Britain’s budget, prompting King George III to squeeze the colonies even harder to pay his debts. Taxation without representation, tea in the harbor, you know the rest.

Many copies of Mitchell’s map have survived, but only three copies marked up at the Treaty of Paris are known to exist. John Jay’s map (several details from which appear above) is held by the New York Historical Society. Richard Oswald’s map was given to King George III and now belongs to the British Library. A French copy of Mitchell’s map was used by the Spanish ambassador at the treaty negotiations; that resides at the National Historical Archive in Madrid. Unfortunately, none of these maps is freely available online.

The influence of Mitchell’s map didn’t stop with the Treaty of Paris. In the 1890s, it was used in negotiations between Canada and the United States over fishing rights in the Gulf of Maine, and it has come into play in legal disputes between eastern US states, as recently as 1932.

In a detailed historical essay (the source for much of this post), Edney calls Mitchell’s map “an irony of empire.” Instead of helping to solidify British control of North America as intended, the map helped set in motion the events that led to the Revolutionary War, and later helped determine the boundaries of an independent United States, a devastating blow to British imperial aspirations on the continent.

–Greg Miller

Many thanks to Ed Redmond at the Library of Congress for suggesting this topic.

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico