You Can Help Make Maps for Science (No Experience Needed!)

With no scientific training, and no clue about cartography, you can help map stuff for science. Lately the opportunities to lend a lay-hand with research seem to be everywhere, and more and more of them involve a mapping component.

This year the results of several citizen-aided science projects hit the news. In May, the researchers behind the Evolutionary Map of the Universe, a project to create a census of galaxies, announced that two Russian citizen scientists had discovered a new cluster of galaxies. In Spain, scientists released a preliminary oral-microbiome map based on participation of more than 4,000 Spanish teens.

The idea of asking the masses for help with science has been around a long time. For some research, humans are the best, or the only option, because computers, algorithms, and AI still can’t beat human brains or global coverage at many tasks. People have been identifying the birds in their backyards every year for almost two decades as part of the Great Backyard Bird Count. The strategy got a boost from a project started in 2006 called Stardust@home that asks people to help search images for the tiny tracks left behind by bits of interstellar dust picked up by a spacecraft. In 2007 the hugely popular Galaxy Zoo project, which involves classifying galaxies according to shape, showed the real promise of involving the public in big labor-intensive projects. Importantly, it revealed that people, lots of people, were excited to pitch in.

These days it’s hard to keep track of all the ways a person can get involved, and more and more of them have geographic or cartographic elements. From tracing neurons to spotting crabs, here are some of our favorite mappy science projects that need your help. (If you have favorites that we left out, please add them in the comments!)

Help Track More than 10,000 of the World’s Bird Species (Global)

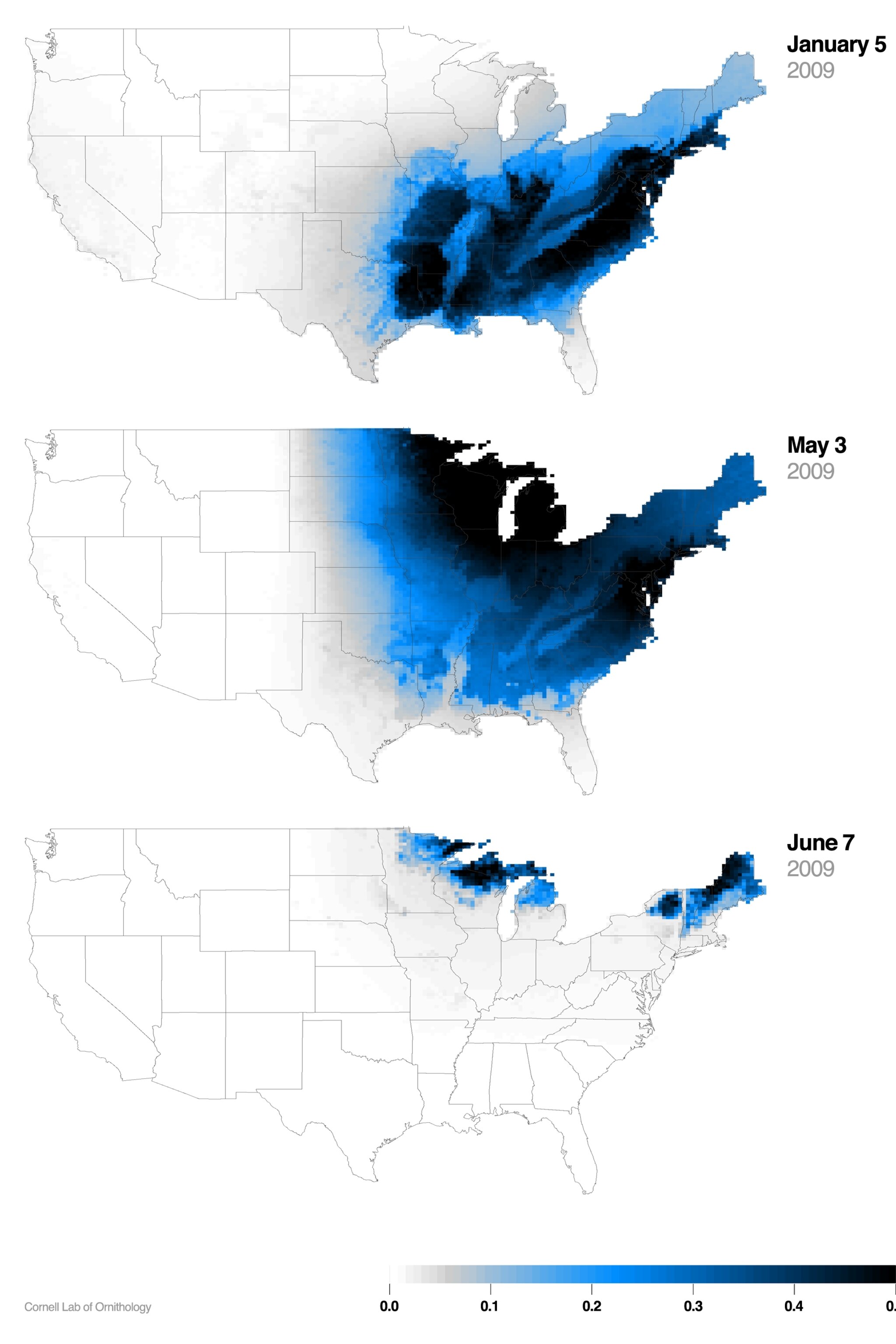

In addition to the Great Backyard Bird Count, which occurs in February every year, another project called eBird tracks citizen bird sightings all year long, all over the world. This project, started in 2002 by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Audubon Society, collects a huge amount of data. In May, for example, bird watchers recorded almost 11.8 million observations, and in June, the grand total surpassed a third of a billion records. The trove of sighting data is made available to any scientists or citizens that want to use it, and has resulted in over 100 publications. The graphic to the right is from a 2011 study based on eBird data that showed how climate change is affecting some birds’ migration routes in North America.

Even if you aren’t an avid bird watcher, or don’t want to record observations, you can enjoy a bunch of maps that have been made with the data, including animated occurrence maps for individual species (like the one at the top of the post), global species distribution maps, hotspot maps, or a real-time map of submissions around the globe.

Help With Earthquake Recovery (Global)

After a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Ecuador on April 16, citizens around the world began analyzing satellite imagery of the region to help with the recovery effort. Calling themselves the Planetary Response Network, a group of institutions led by the European Space Agency asked the public for help through the crowdsourcing platform Zooniverse. More than 2,800 people responded, poring over fresh satellite data provided by Planet Labs (like the image below), and helping to identify where relief on the ground was needed most, and how best to get it there. When the next disaster hits somewhere in the world, you can help too.

And if the earthquake is in your area, you can help the US Geological Survey map the shaking intensity by recording your experience.

The Tea Bag Index (Global)

The rate at which leaves and other organic litter decays seems like a rather boring and esoteric thing to study, but it’s actually important for climate change modeling, because decaying leaves release carbon back into the atmosphere. But leaf decomposition isn’t easy to study because gathering enough comparable data is tough. So researchers at Utrecht University in The Netherlands developed the Tea Bag Index project. To participate, all you need to do is buy some tea bags, weight them, bury them for 90 days, weigh them again and send in the results.

Join the Crab Team (Pacific Northwest)

The European green crab’s native habitat is the northeast Atlantic Ocean and the Baltic Sea, but this little crab has spread to Australia, South Africa, South America, and both coasts of the United States. The crabs can cause considerable problems when they arrive, competing with native fish and shorebirds for food, and threatening the local bivalve populations they prey upon. In Maine, the crab contributed to the destruction of the local soft-shell clam industry, and in the San Francisco Bay Area, the native Manila clam populations have taken a huge hit.

Washington state is understandably concerned as the crab encroaches on its shores. In an attempt to protect the Puget Sound area, which hasn’t yet been invaded, the University of Washington is asking citizens to keep an eye out for any signs of the troublesome crabs, so they can fight back before the critters gain a foothold. If you live in the area, join the Crab Team.

The Feather Map (Australia)

Australia’s wetlands, critical habitat for its waterbirds, is increasingly under threat from a long list of pressures, including land reclamation, climate change, drought and flooding. Now scientists want the public’s help to track where the birds move and which of the remaining wetlands are being used by which species, so they can better plan how to protect the birds. By collecting feathers in wetland areas and sending them in for analysis, people can help build The Feather Map.

Play a Game to Map the Brain (Global)

The Eyewire game involves tracing neurons (see video below) through chunks of brain matter that have been scanned by microscopes in 3D. Apparently it’s much more fun that it sounds — more than 200,000 people from 145 countries have played the game. This incredible participation has given the game’s inventor, Princeton neuroscientist Sebastian Seung, hope that a map of the brain’s connections, known as the connectome, could be completed in two or three decades. As you trace neurons, you aren’t just creating data, you’re also helping to create AI that can map the connectome too.

–Betsy Mason

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico