These 15th-Century Maps Show How the Apocalypse Will Go Down

In 15th-century Europe, the apocalypse weighed heavily on the minds of the people. Plagues were rampant. The once-great capital of the Roman empire, Constantinople, had fallen to the Turks. Surely, the end was nigh.

Dozens of printed works described the coming reckoning in gory detail, but one long-forgotten manuscript depicts the apocalypse in a very different way—through maps. “It has this sequence of maps that illustrate each stage of what will happen,” says Chet Van Duzer, a historian of cartography who has written a book about the previously unstudied manuscript.

The geography is sketchy by modern standards, but the maps make one thing perfectly clear: If you’re a sinner, you’ve got nowhere to hide. The Antichrist is coming, and his four horns will reach the corners of the earth. And it just gets worse from there.

The manuscript is also the first known collection of thematic maps, or maps that depict something that’s not a physical feature of the environment (like rivers, roads, and cities). Thematic maps are ubiquitous today—from rainbow-colored weather maps to the red-and-blue maps of election results—but most historians date their origins to the 17th century. The apocalypse manuscript, which now belongs to the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, was written two centuries earlier, Van Duzer writes in his recently published book, Apocalyptic Cartography.

The manuscript was made in Lübeck, Germany, between 1486 and 1488. It’s written in Latin, so it wasn’t meant for the masses. But it’s not as scholarly as other contemporary manuscripts, and the penmanship is fairly poor, Van Duzer says. “It’s aimed at the cultural elite, but not the pinnacle of the cultural elite.”

The author is unknown. Van Duzer suspects it may have been a well-traveled doctor named Baptista. If so, he was in some ways very much a product of his time, yet in other ways centuries ahead of it.

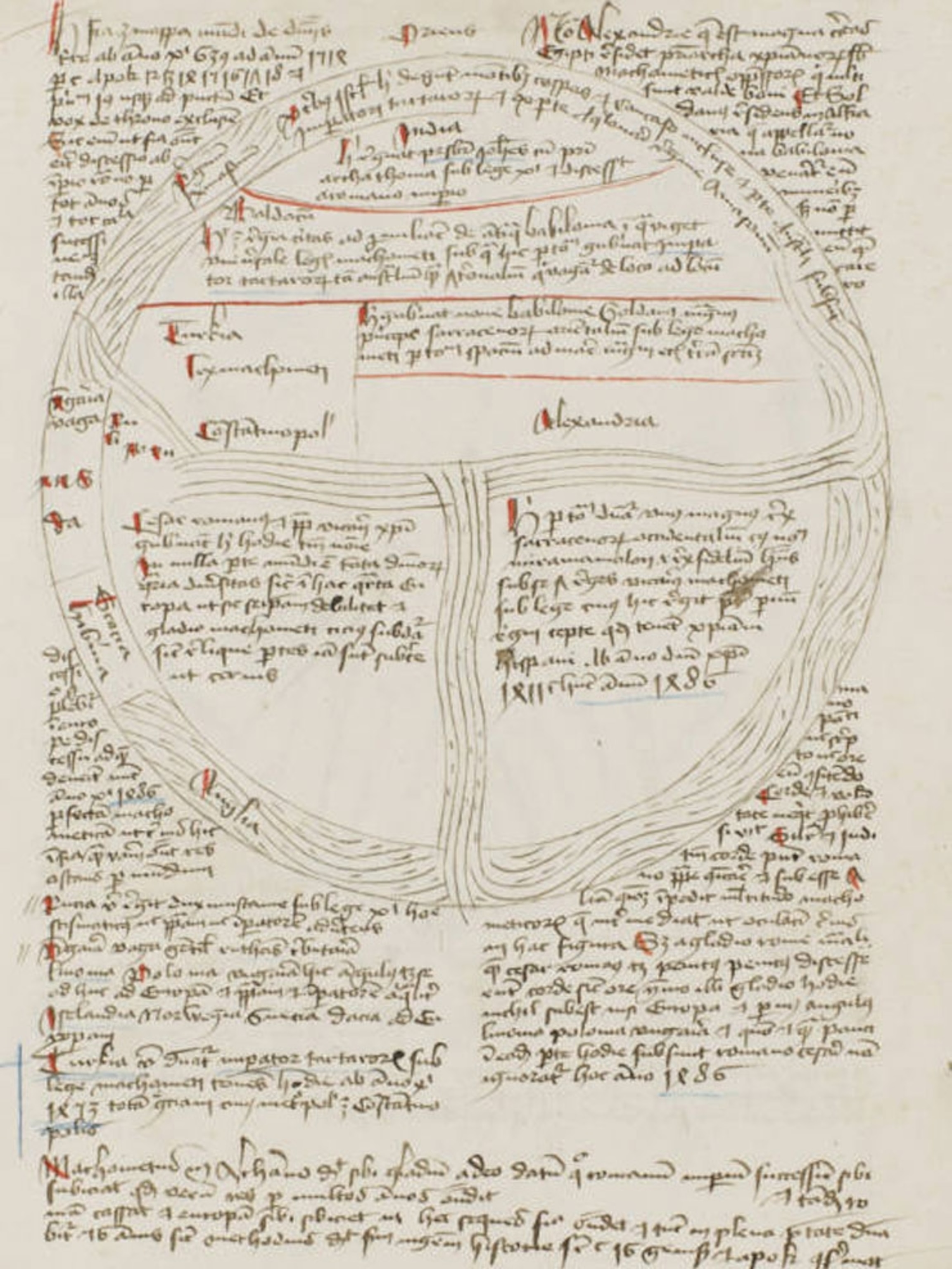

The cartographic account of the Apocalypse begins with a map that shows the condition of the world between 639 and 1514. The earth is a circle, and Asia, Africa, and Europe are depicted as pie wedges surrounded by water. The text describes the rise of Islam, which the author sees as a growing threat to the Christian world. “There’s no way to escape it, this work is very anti-Islamic,” Van Duzer says. “It’s unfortunate,” he adds, but it was a widespread bias in that place and time.

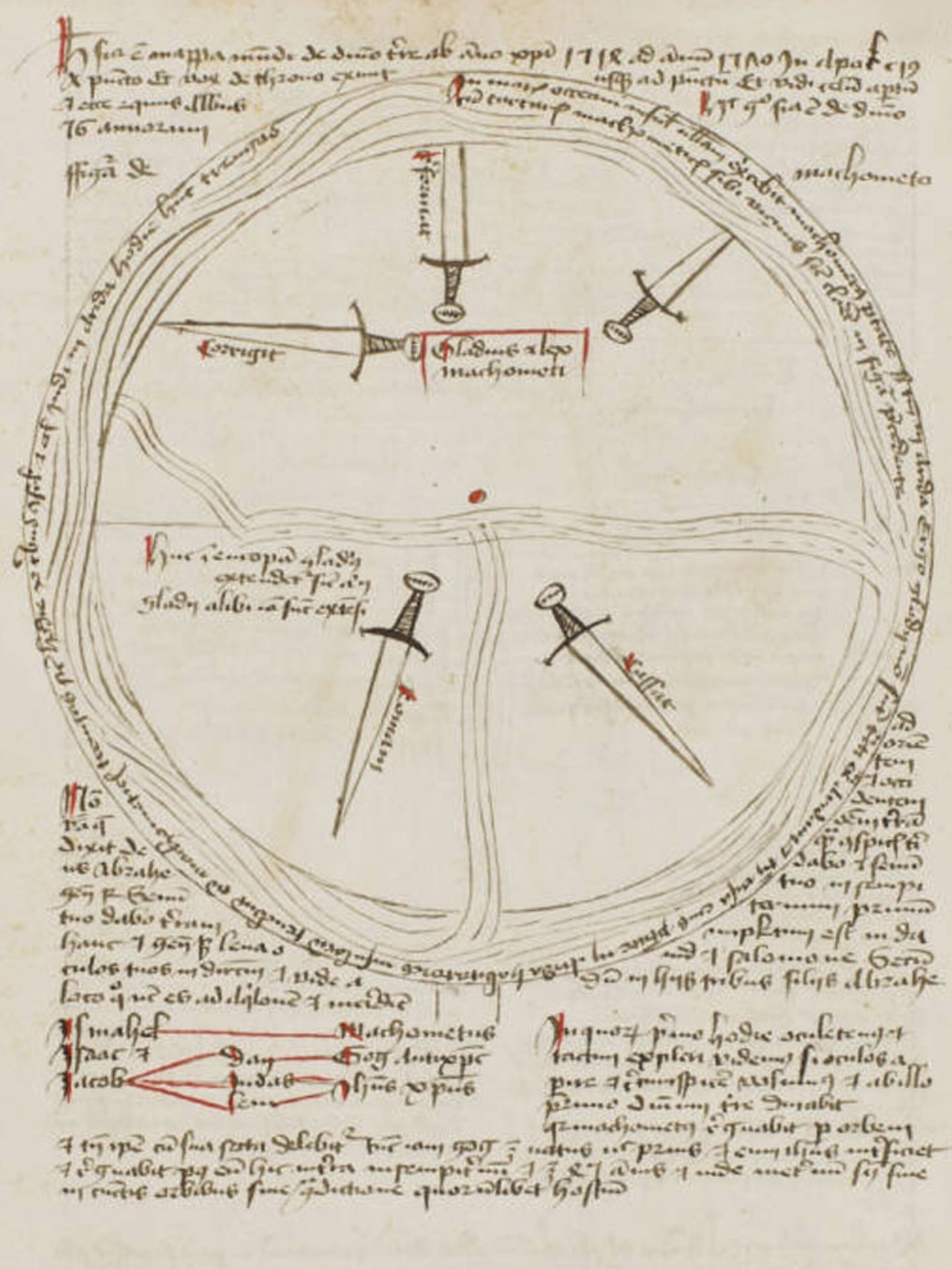

Subsequent maps, which you can see in the gallery above, depict the “Sword of Islam” conquering Europe, followed by the rise of the Antichrist, a massive triangle that extends from pole to pole. Another map depicts the gates of Hell opening up on Judgment Day, which the author predicts will occur in 1651. A small, featureless globe depicts the world after that.

All the maps in the manuscript are symbolic, but the post-apocalyptic map takes minimalism to the max. “There’s nothing on it, but it’s very clearly labeled as a map,” Van Duzer says. “It raises the question of what is a map, and it explores that boundary.”

The text is filled with idiosyncratic details. The author calculated the distance to Paradise: 777 German miles from Lübeck to Jerusalem, and thence another 1000 miles to the eastern end of the Earth (a German mile is an obsolete measurement with many variations, making it difficult to pin down the modern equivalent). He also calculated the circumferences of Earth and Hell (8,000 and 6,100 German miles, respectively, though his use of different numbers for pi suggests a shaky grasp of geometry).

In addition to the apocalyptic section, the manuscript includes a section on astrological medicine and a treatise on geography that’s remarkably ahead of its time. For example, the author writes about the need to adjust the size of text to prevent distortions on maps and make them easier to read, an issue cartographers still wrestle with today. (At the same time, he also chastises mapmakers for placing monsters on maps in places where they didn’t exist, an issue cartographers rarely wrestle with today.)

The geographical treatise ends with a short discussion of the purpose and function of world maps. It’s here, Van Duzer says, that the author outlines an essentially modern understanding of thematic maps as a means to illustrate characteristics of the people or political organization of different regions.

“For me this is one of the most amazing passages, to have someone from the 15th century telling you their ideas about what maps can do.”

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico