Is Drug-Resistant Staph A Work Hazard for Farm Workers?

A new study by the researcher who has done the most to pin down the presence of “pig MRSA” in the United States pries open the relationship between raising animals for food and risking drug-resistant infections—while also demonstrating how frustratingly difficult it is to fill all the data gaps around that risk.

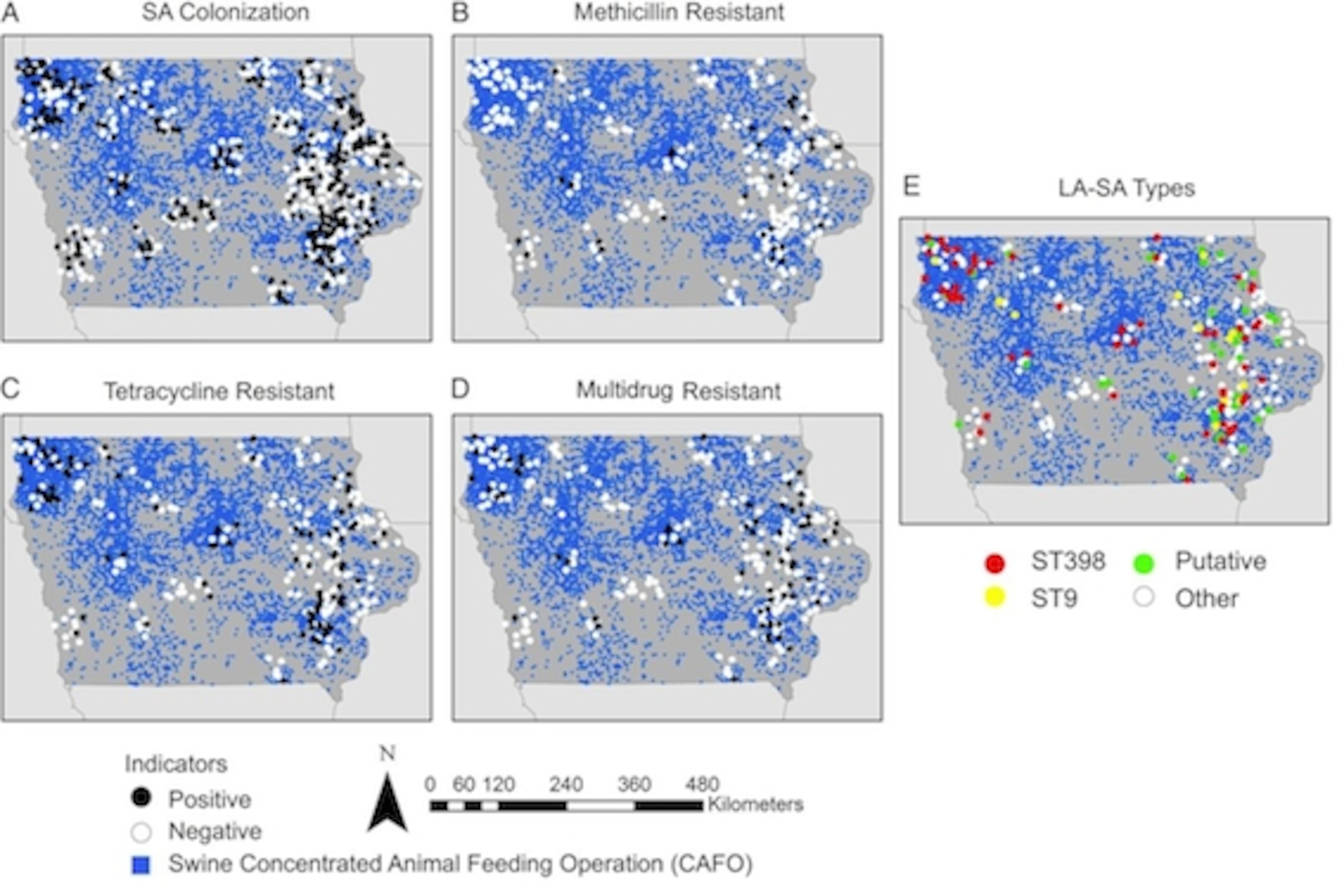

The study is by Tara Smith, who is now an associate professor at Kent State and was previously faculty at thee University of Iowa College of Public Health, where she published the first paper identifying MRSA ST398, the hog-associated resistant strain; her former Iowa colleagues are co-authors. It’s the first study done in the US (and the largest ever) to prospectively track and sample hog farmers, and it maps the results against the locations of hog CAFOs—”confined animal feeding operations” holding thousands of animals—in the state which produces more US pigs than any other.

Quick version of their results: Compared to people with no current swine contact, people currently working with swine were 6 times more likely to be carrying some strain of drug-resistant staph, and 5.8 to 8.4 times more likely to be carrying strains that are specifically linked to hogs.

Those findings do not represent infections—some members of the study population did develop infections, which I’ll get to in a minute—but they represent people at risk of resistant staph infections at some future point. That’s because the single biggest risk factor for developing a staph infection is already being colonized with the germ, that is, carrying it in the nostrils or groin or on the skin.

This is all important because of the ongoing debate, captured in several of my recent posts, regarding how much control we should exert over antibiotics used routinely in agriculture. (And also in this archive from my former blog. And also in this Wired piecethis Wired piecethis Wired piece, not by me, about the data missing from that debate.) Pig MRSA is one of the clearest illustrations of what happens when farm antibiotics are used routinely: Their use created a strain of staph that could be linked back to pigs because it was resistant, not to the drugs usually used in human medicine against staph, but to a drug given to pigs as a growth promoter.

The terminology around staph is complicated, so to define terms a bit: The study looked for staph; MRSA, or methicillin-resistant staph, the major form of drug-resistant staph, which is primarily resistant to one large class of antibiotics, the beta-lactams (encompassing the drug families penicillins and cephalosporins); MDRSA, or “multi-drug resistant” staph, which is MRSA that has picked up resistance to additional drug families; LA-SA, or “livestock-associated” resistant staph, which has a particular genetic signature known as ST398 and was first identified in pigs in the Netherlands in 2004; and TRSA, or tetracycline-resistant staph. (Tetracycline is one of the most-used drugs in swine raising, and the original livestock associated strain was tetracycline-resistant.)

Here’s Smith, in a post on her own blog about the paper, about the history and importance of ST398:

…work from my lab has shown that, first, the “livestock-associated” strain of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) that was found originally in Europe and then in Canada, ST398, is in the United States in pigs and farmers; that it’s present here in raw meat products; that “LA” S. aureus can be found not only in the agriculture-intensive Midwest, but also in tiny pig states like Connecticut. With collaborators, we’ve also shown that ST398 can be found in unexpected places, like Manhattan, and that the ST398 strain appears to have originated as a “human” type of S. aureus “human” type of S. aureus “human” type of S. aureus which subsequently was transmitted to and evolved in pigs, obtaining additional antibiotic-resistance genes while losing some genes that help the bacterium adapt to its human host. We also found a “human” type of S. aureus, ST5, way more commonly than expected in pigs originating in central Iowa, suggesting that the evolution of S. aureus in livestock is ongoing, and is more complicated than just ST398 = “livestock” Staph.

Smith goes on to say that the unanswered question in all this research was how often pig-related resistant staph caused infections in people. This study was designed to begin answering that. Here’s what it found: Out of 1342 participants, 351 or 26.2 percent were carrying some form of staph in their noses or throats, among which:

- 34 were carrying MRSA;

- 68 were carrying MDRSA;

- 131 carried LA-SA, the classic livestock MRSA type;

- 86 of the LA-SA strains were TR, tetracycline resistant.

The researchers followed the participants for 17 months. Over that time, 67 of them reported 103 skin infections, 22 of them sent in swabs of the infections for analysis, 10 were positive for MRSA, and 3 of the 10 were ST398. But those numbers, Smith said, don’t necessarily reflect the incidence of MRSA or livestock-related strains because of these issues: farmers resist going to the doctor; not all infections are analyzable (a common presentation, cellulitis—a raised rash—doesn’t produce the pus needed for a culture); and most physicians diagnose staph by sight, not culture or type-test. So the study couldn’t benefit from physicians’ reports on participants who didn’t send in swabs, but did go to their doctors.

That’s a glimpse into the difficulty of amassing sufficiently granular data to shine a light on this problem. Here are some others, which the study acknowledges. Most of the study participants were owner/operators of smaller farms (median: 355 animals), not workers on the vast intensive CAFOs for which Iowa is famous; so while it’s a reasonable assumption that intensive farms using antibiotics would produce more drug-resistant bacteria, the study can’t demonstrate that. Similarly, this study tested only workers, not the animals; so the researchers can’t draw direct links between resistant bacteria in the workers and in the animals they are handling, and also can’t pin down the influence of CAFOs putting resistant bacteria into the local environment.

What it does do is draw a firm association between recent exposure to swine, and greater probability of acquiring resistant bacteria. In the ongoing debate over the risks of using agricultural antibiotics, that is a useful thing to know.

Cite: Wardyn SE, Forshey BM, Farina SA. Swine Farming Is a Risk Factor for Infection With and High Prevalence of Carriage of Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus.Swine Farming Is a Risk Factor for Infection With and High Prevalence of Carriage of Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Infectious Diseases, first published online April 29, 2015. doi:10.1093/cid/civ234.

Go Further

Animals

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- When America's first ladies brought séances to the White HouseWhen America's first ladies brought séances to the White House

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

Travel

- Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?

- How to navigate Nantes’ arts and culture scene

- Paid Content

How to navigate Nantes’ arts and culture scene - This striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotelsThis striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotels

- Photo story: a water-borne adventure into fragile AntarcticaPhoto story: a water-borne adventure into fragile Antarctica