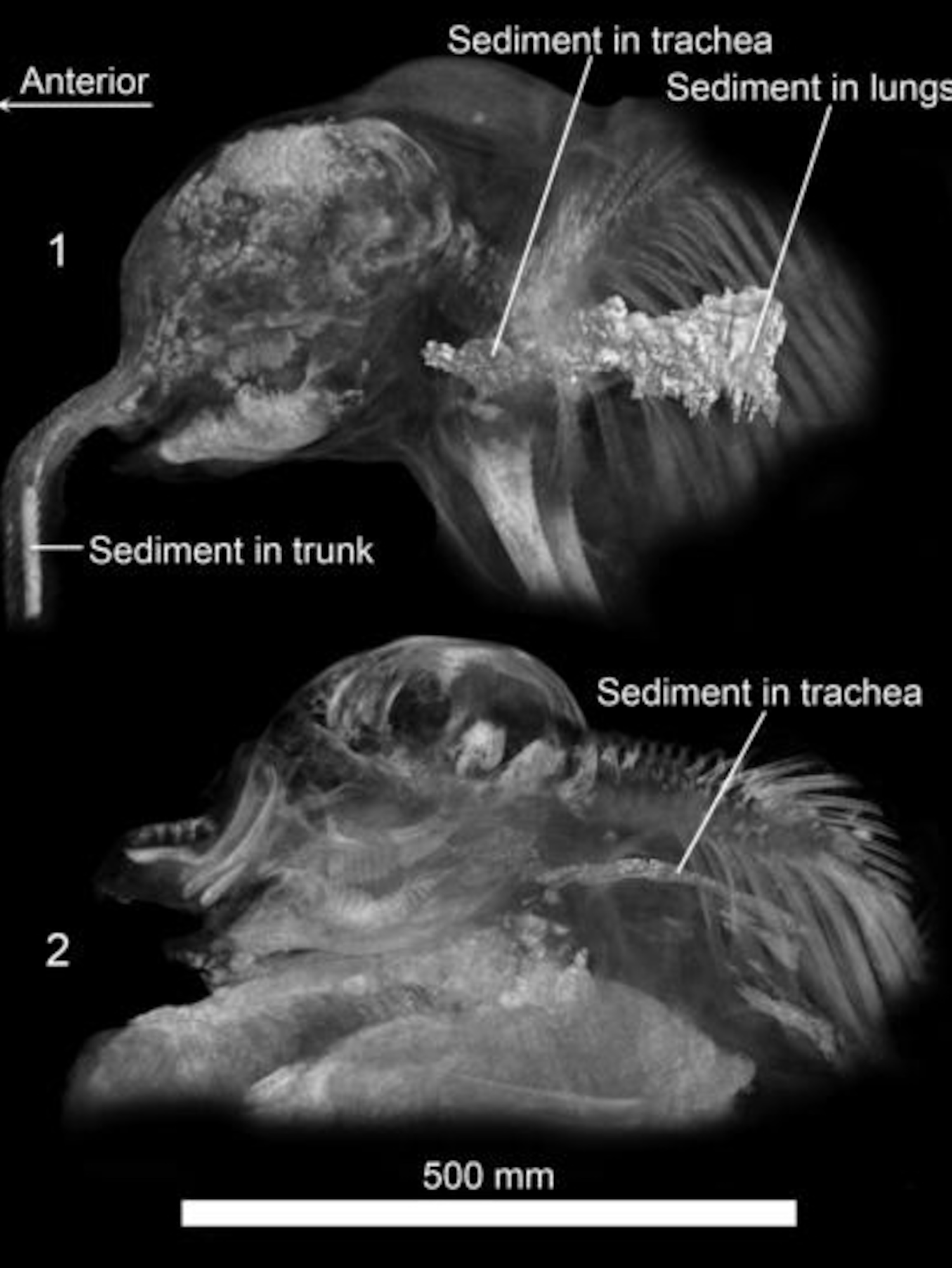

There’s only one fossil that ever made me cry. Lyuba, a one month old woolly mammoth, made me a little misty-eyed when I visited her body at New Jersey’s Liberty Science Center in October of 2010. She was beautiful, intact down to hairs in her little floppy ears, but the entire reason her body retained its composure was because Lyuba suffered a tragic death. Somehow she suffocated in Ice Age mud, coming to rest in the chilled mire. Even though I couldn’t see it, there was still sediment in her throat and lungs when I visited her corpse.

What I didn’t know was that Lyuba wasn’t unique. Not long after Lyuba’s discovery in 2007, paleontologists announced the discovery of a second Siberian mammoth calf mummy nicknamed Khroma. This second specimen was about a month older than Lyuba, but she died in almost the same way. Khroma, too, had suffocated to death.

Despite some damage caused by scavenging dogs and postmortem pecks by crows, respectively, Lyuba and Khroma are the best-preserved mammoths in the world. Other mammoth carcasses – such as seven month old Dima – have degraded over time or aren’t anywhere near as complete. And despite their tragic fate, Lyuba and Khroma were found at a time when science could see inside them without doing extensive, invasive dissections. Using CT scan technology, University of Michigan mammoth expert Daniel Fisher and colleagues have been able to investigate Lyuba and Khroma from the inside out.

Fisher and coauthors have published their findings in the Journal of Paleontology, laying out details briefly presented by Ethan Shirley and Fisher at the 2011 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. Despite being so close in age, the little mammoths are surprisingly different. Lyuba’s skull is much narrower compared to Khroma’s, and the bones at the front of her upper jaw – the premaxillae – have a comparatively thin, pinched form.

Time and space may account for the disparity. Both Lyuba and Khroma lived and died over 40,000 years ago, but they didn’t live at exactly the same time. The two little mammoths also lived about 3,000 miles apart from one other. The differences in their skulls, Fisher and colleagues suggest, could be the result of variation between mammoth populations separated by centuries and thousands of miles.

But age matters, too. Even though Lyuba died at about 35 days after birth and Khroma perished at around 57 days old, baby mammoths grew quickly. The anatomical differences could reflect differences in age as well as population differences.

If only Lyuba’s skull were better preserved! Khroma’s CT scan showed that the baby mammoth had a brain volume of about 2,300 cm3, a little less than that of modern elephants of about the same age. Such a measurement for Lyuba would have allowed paleontologists to get a rough handle on how mammoth brains changed early in life.

The new study didn’t only reveal details of mammoth lives, though. The scans also allowed Fisher and coauthors to get a more refined view of what happened to Lyuba and Khroma.

The sediment inside Lyuba’s respiratory tract included a blue mineral called vivianite. This mineral can form in the oxygen-depleted bottom waters of cold lakes, hinting that Lyuba died in such frigid waters. Additional vivianite formed in other places on her body after she perished, too, but nodules of the mineral on her skull hint at a chilling twist.

In a previous study, Fisher and coauthors suggested that as Lyuba was struggling to breathe, the mammalian “diving reflex” kicked in as a last ditch attempt to get her out of trouble. This would have shut down blood flow to much of the outer surfaces body, with the exception of the head. Sadly, it didn’t work. When Lyuba died, the blood that remained in her head became an iron source for vivianite to grow.

Khroma’s end was different. A previous dissection of her body found milk in her stomach, meaning that she had nursed shortly before her death. No one knows exactly what happened, but the combination of a spinal injury and suffocation hint that the little mammoth was caught in a mud flow or suddenly fell when the bank of a waterway collapsed, breaking her bones and causing the undoubtedly panicked mammoth to suffocate. A tragedy for Khroma and her mother, but an event that, tens of thousands of years later, has given paleontologists a rare understanding of a beast we can no longer see alive.

Reference:

Fisher, D., Shirley, E., Whalen, C., Calamari, Z. Rountrey, A., Tikhonov, A., Buigues, B., Lacombat, E., Grigoriev, S., Lazarev, P. 2014. X-ray computed tomography of two mammoth calf mummies. Journal of Paleontology. 88, 4: 664-675

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest