Out in the field, paleontologists save fossils. Even the most resilient fossils face destruction by erosion and time, and researchers balance speed and care in trying to excavate the history of life on Earth before it crumbles away into petrified shards. But paleontologists have become increasingly concerned with saving fossils from another sort of loss. Already-excavated fossils can land beyond the reach of scientists through public auctions, commercial sales, and black market deals, preventing those ancient remains from spilling their secrets. Thankfully, though, this week paleontologists got news that two different sets of fossils have been saved for science.

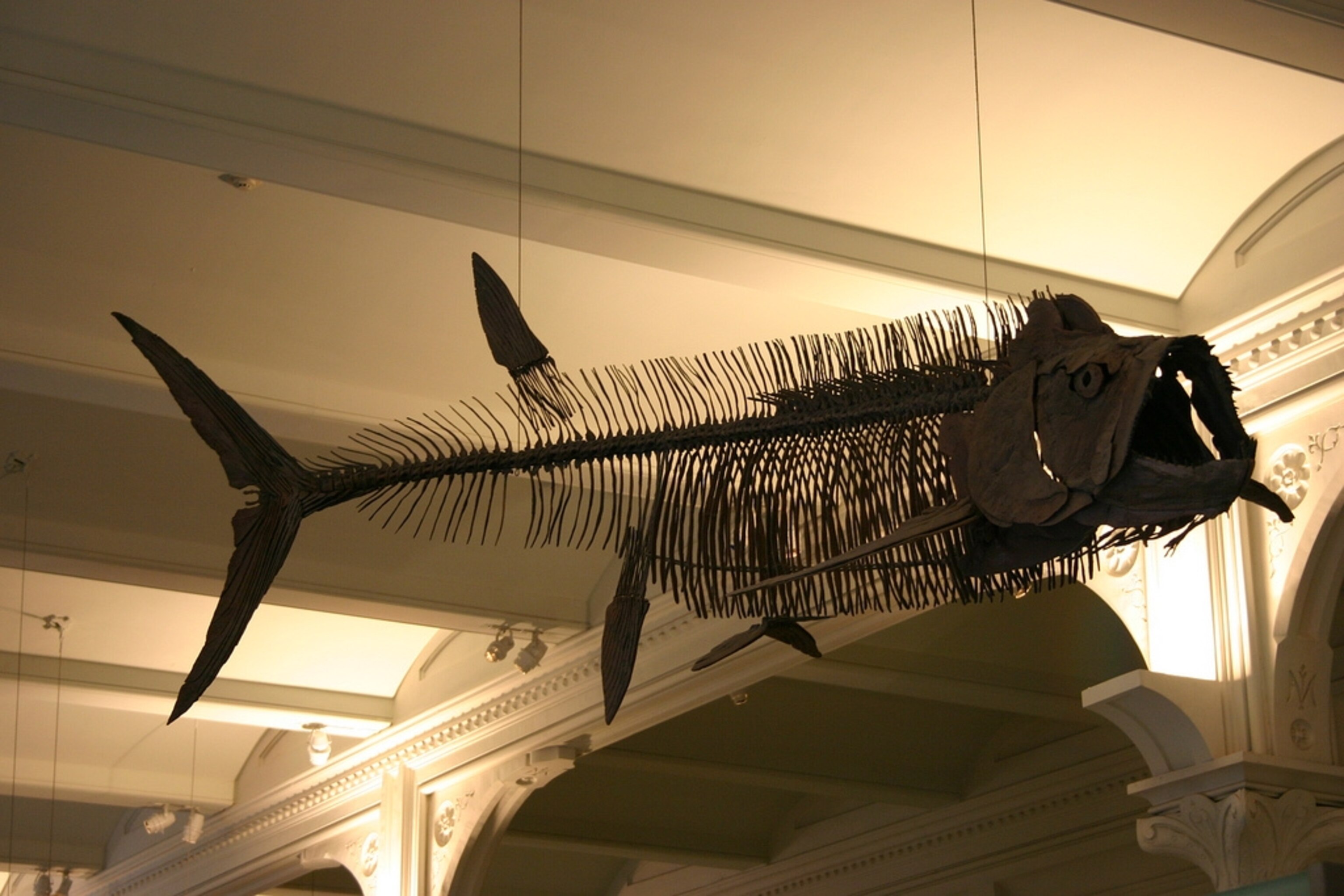

Last November Bonham’s was getting ready to auction off a set of Cretaceous fossils that had been collected by the famous bone sharp Charles H. Sternberg and housed at the San Diego Natural History Museum. Paleontologists decried the scheduled sale. The lots listed included specimens such as a mosasaur and “bulldog tarpon” that not only had historic importance for their connection with Sternberg, but also held scientific value in that they had been researched before. Paleontology relies on continued access to specimens so that scientists can check and reinvestigate what has been studied before – reproducibility is key – and so experts acted quickly to try to halt the auction.

Fortunately, the San Diego museum agreed to pull the lots and worked with other institutions to relocate Sternberg’s fossils. Alberta, Canada’s Royal Tyrrell Museum quickly arranged to take in the skull of Chasmosaurus, a horned dinosaur, that had been taken off the auction block, and just this week the Museum at Prairiefire in Overland Park, Kansas announced that they will be a new home for five of the other specimens previously housed in San Diego. Two of those – a skeleton of a carnivorous seagoing lizard named Platecarpus and the giant fish Xiphactinus – will go on display there next month. Thanks to this cross-institution collaboration, Sternberg’s fossils will remain open to scientific exploration and public fascination.

But the most joyous fossil news of the week has to do with the bones of a mysterious dinosaur that is just getting ready to emerge from the scientific shadows.

Just weeks before scientists rushed to halt the auction of Sternberg’s fossils, at the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Los Angeles, California, paleontologist Yuong-Nam Lee unveiled the body of a dinosaur named Deinocheirus. If you were a little dinomaniac during the 80s and 90s you’ll remember this creature as nothing more than a pair of disembodied arms with huge claws. No one knew what the rest of the animal looked like. But at the SVP meeting, Lee announced that he and his colleagues had found two new Deinocheirus skeletons. This was an absurd, 40-foot-long dinosaur with a long neck, huge arms, and a humpback, but Lee reported that the feet and skulls of the skeletons were nowhere to be found. Poachers had removed them before his team had been able to extricate the dinosaurs.

At least one set of the missing fossils had been smuggled out of Mongolia and wound up in the collection of an as-yet-unnamed private collector. How that happened has not been revealed. But the good news, reported by Jeff Hecht in New Scientist, is that French fossil dealer François Escuillié spotted the fossils, and, after verifying their identity with paleontologist Pascal Godefroit and members of the team that led the recent scientific expeditions, Escuillié purchased the skull and feet to donate to the Mongolian government. The bones perfectly match one of the headless skeletons Lee described, finally reuniting them.

The repatriated Deinocheirus bones will be in good company. They will be housed at the Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs in Ulaanbaatar, the slated home of a reconstructed Tarbosaurus that was almost sold into private hands in 2013. From a mosasaur that now rests close to where it was excavated to a dinosaurian enigma that has been recapitated, it’s heartwarming to see these fossils go home.

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest