For millions of years, there were birds with false teeth. I do not mean dentures. That would be terrifying. No, a particular subgroup of birds called the Odontopterygiformes were the sole group of birds to evolve tooth-like spikes along their beaks in a sinister avian grin. Of these birds, which originated about 56 million years ago, among the largest and most recent was the 2.5 million year old bird Pelagornis mauretanicus. Known from fossils found in Morocco, this soaring avian looked something like an albatross with a serrated beak. But, if not teeth, what were those spikes and how did they grow?

The earliest birds had true teeth. Naturalists have known this since the late 19th century, and this transitional feature is now one of a collection of traits connecting archaic birds with their feathery, non-avian dinosaur precursors. Over the course of Mesozoic time, however, multiple lineages of early birds evolved totally toothless beaks. Why this should be so isn’t entirely clear. The evolution of beaks may have constrained and ultimately halted tooth development, while gizzards took over a food-processing role internally. Whatever the reason, though, there hasn’t been a true toothy bird since the end-Cretaceous mass extinction wiped out the last of them about 66 million years ago.

Once birds evolved toothless beaks, avians lost those specific dental tools forever. That evolutionary pathway is closed to them. True, embryonic chickens can grow tiny, nascent tooth nubs, but the natural mutation is lethal and prototeeth that are induced by laboratory manipulation are resorbed back into the beak later in development. Genetic and developmental changes have barred birds from re-evolving true teeth made of dentin and enamel. Yet, for some birds, having a mouth full of spikes or ridges to grab food could be quite handy. This is where Pelagornis and kin come in. With teeth totally lost, the bones and beaks of these birds evolved novel structures that mimicked the long-lost teeth of their ancestors.

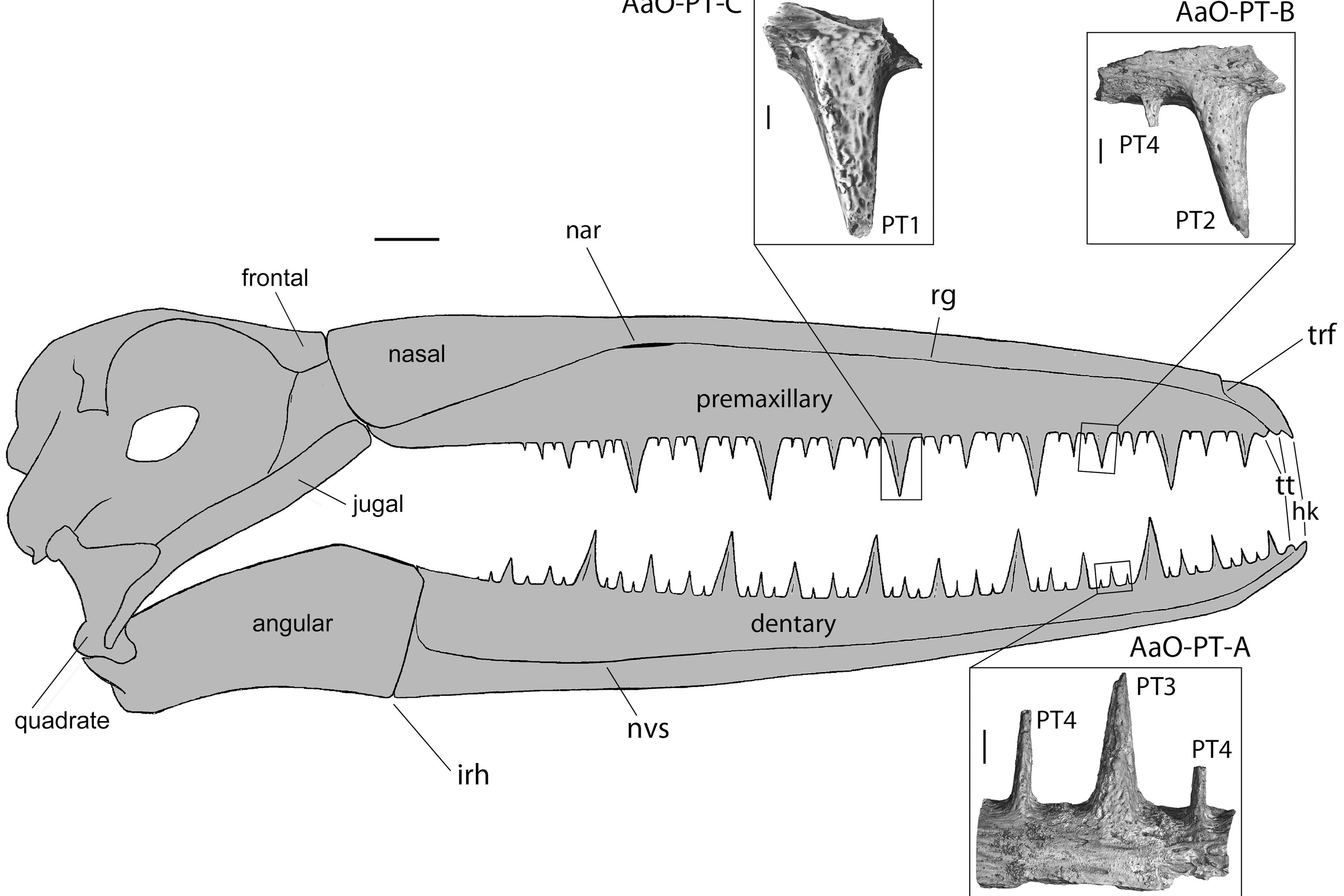

In a new PLoS One study, Université Lyon tooth development expert Antoine Louchart and colleagues looked inside the jaws of Pelagornis mauretanicus to see what these structures truly were. The spikes along the bird’s jaws certainly weren’t true teeth. There was not a trace of dentin, enamel, or other characteristic tooth tissues. The low and high spines were made of true bone attached to the jaw and would have been covered by the same tough, flexible material of the rest of the beak in life.

How Pelagornis grew such a spiky snarl isn’t entirely clear. The species in the study and others within the genus are only known from relatively rare bits and pieces. No one has yet put together a growth series from hatchling through adult for these birds. But, based upon their study of the available jaws, Louchart and coauthors expect that juvenile Pelagornis would have looked quite different from the adults.

The hollow teeth of Pelagornis were not secondarily fused to the jaw, but appear to have grown out of the jaw itself. The question is how and when they did so. One possibility is that the bird’s pseudoteeth developed as the jaw itself grew and changed shape. But, the researchers point out, such a scenario raises problematic questions about the details of bone growth. More likely, Louchart and colleagues propose, the pseudotooth only started to develop after the jaw finished growing. As the outside of the spike built up, the inside was resorbed, and the keratin sheath surrounding the beak finally hardened once the spikes grew.

How spiky the jaws of Pelagornis looked in life depends on how the beak covered the pseudoteeth. Some of the smaller spikes, the researchers suggest, may not have been tall enough to create a point on the beak. But this may have only been the look of adult animals. The young birds may not have had any spikes at all, meaning young Pelagornis weren’t adept at gripping struggling fish with their weak, smooth jaws..

If Louchart and colleagues are correct about the late growth of pseudoteeth in Pelagornis, the young birds either relied on their parents for food for an extended amount of time or they targeted soft food different from what the adult birds were after. Which scenario is closer to how these remarkable birds actually lived is unknown and, as ever, relies of future fossil discoveries. Nevertheless, Pelagornis is a striking example of alternative evolution. Evolution does not offer unlimited possibilities, yet the way nature weaves around developmental barriers and historical constraints has resulted in a history of life on Earth that is far stranger than anything we could have imagined.

References:

Louchart, A., Viriot, L. 2011. From snout to beak: the loss of teeth in birds. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 26, 12: 663-673

Louchart, A., Sire, J., Mourer-Chauvire´, C., Geraads, D., Viriot, L., de Buffrénil, V. 2013. Structure and growth pattern of pseudoteeth in Pelagornis maurentanicus (Aves, Odontopterygiformes, Pelagornithidae)Structure and growth pattern of pseudoteeth in Pelagornis maurentanicus (Aves, Odontopterygiformes, Pelagornithidae)Structure and growth pattern of pseudoteeth in Pelagornis maurentanicus (Aves, Odontopterygiformes, Pelagornithidae). PLoS One. 8, 11: e80372

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?