On May 27th, 2010 paleontologists Martin Smith and Jean-Bernard Caron announced that they had found a spectacular solution to one of the fossil record’s long-running mysteries. Since its description in 1976, the 505 million year old fossil Nectocaris pteryx from British Columbia’s famous Burgess Shale had vexed scientists. Known from a single specimen – appearing as little more than a smear on a rock slab – this creature seemed to be equal parts chordate and arthropod. No one could say what it was. Thanks to the discovery of nearly 100 additional specimens, however, this Cambrian oddball could finally be reexamined and its affinities resolved. In the pages of Nature, Smith and Caron presented Nectocaris as the early, Cambrian cousin of all other cephalopods, informally promoted as the ur-squid.

Given that Nectocaris had been inspiring “WTF?” moments among paleontologists for over twenty five years, you might think that its resolution as “the mother of all squid” would have been excitedly welcomed. The fantastic life restoration by Marianne Collins – the most prominent illustrator of the Burgess Shale fauna – was exciting enough alone! But other paleontologists were skeptical of the new squid on the block. In the comment thread of Ed Yong’s well-written post on the discovery, paleontologist Thomas Holtz was the first to remark that the new, clearer specimens of Nectocaris looked awfully similar to a group of well-known Burgess Shale creatures more closely related to arthropods called anomalocaridids. Doubts and caveats were also expressed elsewhere among the blogohedron – the new specimens had radically changed the general image of Nectocaris, but the stem-cephalopod hypothesis could not be affirmed beyond the shadow of a doubt.

Rather than being the exception, this ongoing state of debate is the rule for Cambrian fossils. Restorations of creatures the Burgess Shale fossils represent – as well as the biological and evolutionary interpretations drawn from them – have been in a near-constant state of flux since Charles Doolittle Walcott started discovering them in 1909. It has only been within the last thirty years that paleontologists have been able to piece together the actual forms of many of these enigmatic animals, but there are still a number of open-cases that continue to frustrate researchers. Nectocaris is just one of them.

The tangled tale of Nectocaris began during the early 20th century. The first specimen ever found – and, for a time, the only specimen known – was collected by Walcott sometime during his collecting trips to the Burgess Shale. He left no notes about its discovery, and he never published on it. It was not until 1976 that the British paleontologist Simon Conway Morris described it and gave the creature its name.

Just what Nectocaris was, though, Conway Morris couldn’t say. The head of the creature looked shrimp-like, but this was followed by a narrow, tapered body with fringe-like fins running along the top and bottom. There was simply nothing else like it. Conway Morris wisely decided to leave its systematic assignment uncertain, but, now that the specimen had been published, other researchers were able to propose alternate interpretations.

In 1988 Alberto Simonetta proposed that Nectocaris was an early chordate – an archaic cousin of the first vertebrates which evolved much later. In overall form and in some specifics the anatomy of Nectocaris appeared to resemble that of lancelets such as Branchistoma, although this interpretation did not catch on. Published a year later, Stephen Jay Gould’s Wonderful Life reaffirmed the oddball nature of this animal, and although Gould highlighted some of the purported chordate traits he, too, left Nectocaris in systematic limbo. No one quite knew what to make of this creature with an arthropod head and an eel-like body. More specimens were required to determine whether the various traits perceived by the scientists were flukes or real anatomical parts.

The 91 new specimens reported by Smith and Caron have done much to alter our image of Nectocaris. It mostly came down to a matter of perspective. Although they could not have known it from just one specimen, Nectocaris actually had a compressed body which was flattened from side-to-side. The right side of the specimen was really the bottom. Likewise, the head of the original specimen was incomplete and twisted with respect to the rest of the body, giving Nectocaris a shrimp-like profile that it did not actually have in life. This sort of thing has happened before. When Conway Morris described the enigmatic creature Hallucigenia he reconstructed it as walking on its spines with tentacles stemming from its back, but in 1991 paleontologists Lars Ramskold and Hou Xianguang flipped it over. The feeding tentacles were actually tube feet, and the spines jutted out of the animal’s back.

But the makeover Smith and Caron gave Nectocaris was more than just cosmetic. Their restoration also carried some evolutionary hypotheses along with it. Based upon the diversity and disparity among the shelled nautiloids and other fossil cousins of squid and octopus, it was expected that cephalopods existed during the Cambrian. These squishy fossils proved elusive, but Nectocaris was a good candidate for the archaic stem group from which the first cephalopods evolved. This means that it was not a cephalopod itself, but one of the forms on the long branch which rooted true cephalopods to their last common ancestor with other molluscs.

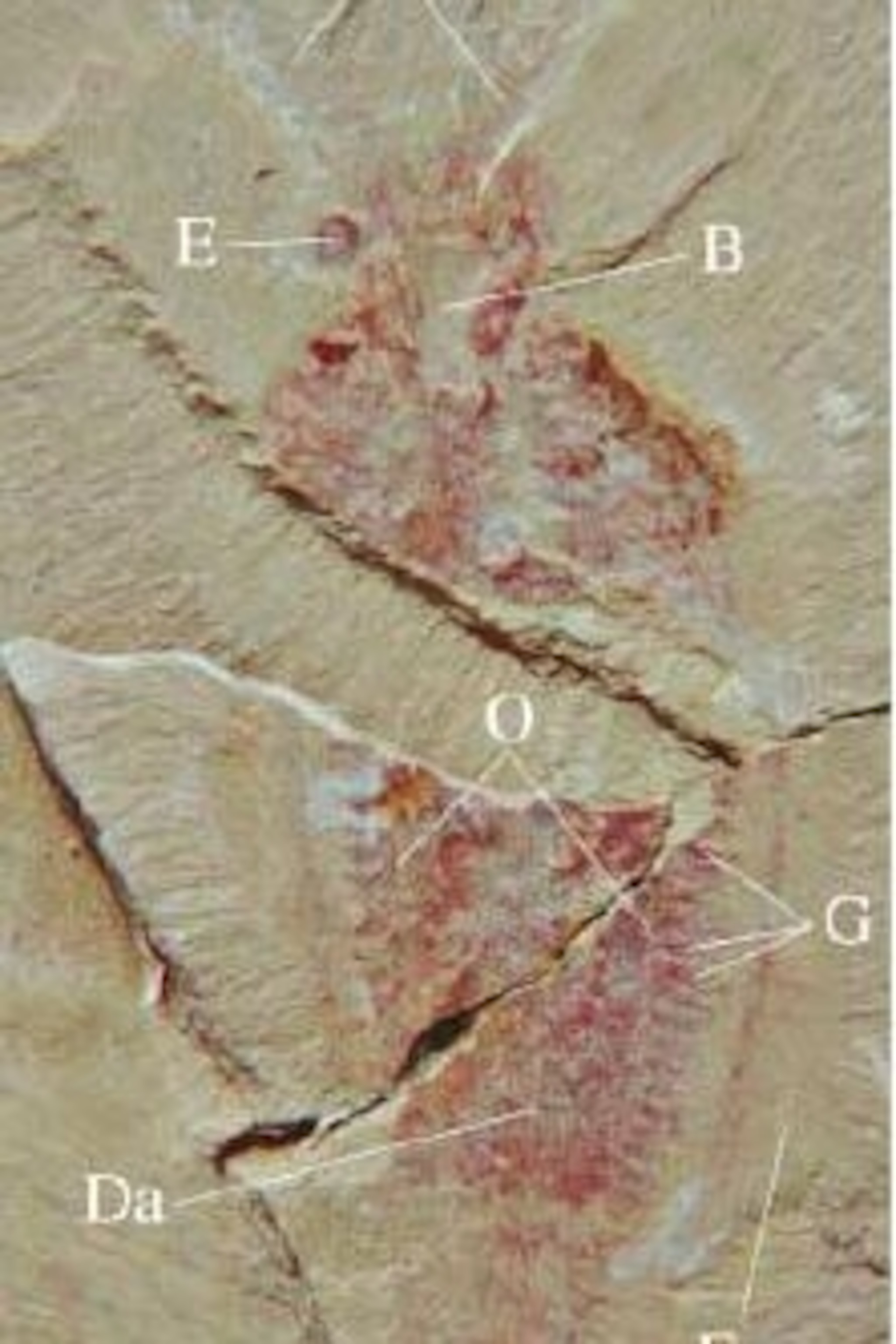

The identity of Nectocaris as a stem-cephalopod rested on a mosaic of characters. Nectocaris appeared to possess two tentacle-like appendages in front of the head, had a pair of camera eyes (not compound eyes like those seen among arthropods), and many fossils seemed to preserved a flexible funnel which would have been used for jet-propulsion.

But there are a few problems with this hypothesis. Among them was the location of the mouth in Nectocaris. This important feature went unidentified in the Nature paper. Smith and Caron mention “a symmetrical dark region” that is “sometimes evidence at the anterior of the head, between the tentacles”, but the actual identity of this smudge is unclear. Instead, the “funnel” may be part of a flexible feeding apparatus which has been misidentified. Despite being given a new look, Nectocaris was as difficult to interpret as ever.

The new shape of Nectocaris was quite different from the way it had traditionally been reconstructed, but its shape was not unknown to paleontologists. In 2005 Jun-yuan Chen, Di-ying Huang, and David Bottjer reexamined the problematic Early Cambrian fossil Vetustovermis, found in southern China. It was originally interpreted as a annelid worm or an arthropod, but the analysis of 17 additional specimens seemed to rule out these hypotheses. Much like the newfound specimens of Nectocaris, the Vetustovermis fossils preserved a flattened body fringed by undulating fins on either side, eyes on short stalks, and two tentacle-like appendages extending in front of the head. Pairs of bars which ran down the body of the organism, originally proposed to be body segments, were reinterpreted as gills, and the scientists interpreted a structure on the bottom of the body as a kind of squishy foot seen among mollusks. Overall, Vetustovermis exhibited a suite of characters which could be interpreted in various ways and gave no clear sign as to what animal group it belonged to – many of its features, such as the stalked eyes and gooey foot, are seen in other groups of organisms. Significantly, however, Huang and co-authors recognized that this confounding creature might share some important similarities with Nectocaris, writing:

Similar animals have also been recorded from Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Several Burgess Shale problematic creatures, including Nectocaris (Conway Morris 1976), Amiskwia (Walcott 1911), and Odontogriphus (Conway Morris 1976), are likely candidates for interpretation as Vetustovermis-like soft-bodied animals. Although the single specimen of Nectocaris has been viewed as laterally compacted, we suspect that it is a subdorsally compacted specimen. If this alternative interpretation is correct, the resemblance with Vetustovermis is thus striking by sharing a number of features including a slug-like head that carries a pair of cephalic tentacles and stalked eyes, a trunk that was laterally finned with a triangular anterior portion, and a large number of transverse gills spread over most of the trunk.

Chen and colleagues were correct. The wealth of Nectocaris reported by Smith and Caron last year indicated that the original Nectocaris specimen was preserved in such a way that its true form was obscured , but just what the animal actually was another matter. Whereas Smith and Caron believed the animal to be a cephalopod, earlier this year Dawid Mazurek and Michal Zaton published a brief note in the journal Lethaia supporting the anomalocaridid hypothesis. (These creatures, represented by Anomalocaris and kin, were segmented invertebrates with grasping appendages, stalked eyes, and circular mouths.) The features which would seem to link Nectocaris with squid, Mazurek and Zaton wrote, were only superficial similarities, though the scientists held back from trying to formally reassign the frustratingly enigmatic animal. Even though the anomalocaridid hypothesis would seem to be a better fit, the evolutionary history of these creatures is still being worked out. More fossilized context is required to know how Nectocaris relates to them.

Whatever Nectocaris is, though, the case for it being a cephalopod looks weak. Last month researchers Björn Kröger, Jakob Vinther, and Dirk Fuchs published a review of cephalopod evolution, and they included a subsection on the disputed identity of Nectocaris. Calling the creature “a lost child of the Cambrian”, Kröger and co-authors noted that the image of a soft-bodied, free-swimming cephalopod at the root of the group’s family tree runs counter to embryology and the rest of the fossil record. Together, these two lines of evidence indicate that shells were an early cephalopod trait, and it was only after chambered shells allowed these molluscs to start swimming freely did the shell become reduced and internalized. If Nectocaris was truly a cephalopod, then a derived, squid-like body evolved first, was lost, and then appeared a second time at some later date – a scenario inconsistent with the big picture of cephalopod evolution as is presently understood.

More than that, some of the supposed cephalopod traits of Nectocaris appear to have been misinterpreted. For one thing, the structure identified as a funnel is very small and narrow. Therefore Kröger and colleagues contend that “the supposed axial cavity and the funnel [of Nectocaris] could not function as either a respiratory or jet propulsion system” as in cephalopods. The structure in question appears to be some part of the animal’s digestive system that could be everted outside the body. Rather than being a cephalopod, therefore, the researchers proposed that Nectocaris and similar creatures – like Vetustovermis – may represent other lineages within the major animal group called the Lophotrochozoa which independently converged on a cephalopod-like body plan.

The evolutionary identity of Nectocaris is just as mysterious as ever. Even though paleontologists have gained a more accurate picture of what this animal generally looked like, where the animal fits in the tree of life remains uncertain. That Nectocaris was a dawn squid is doubtful, but whether it was an anomalocaridid, some unknown type of lophotrochozoan, or held membership in some other group has yet to be determined. As Nectocaris beautifully demonstrates, the Cambrian was an evolutionary wonderland full of strange creatures we are only truly just beginning to understand.

References:

Chen, J., Huang, D., & Bottjer, D. (2005). An Early Cambrian problematic fossil: Vetustovermis and its possible affinities Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272 (1576), 2003-2007 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3159

Kröger, B., Vinther, J., & Fuchs, D. (2011). Cephalopod origin and evolution: A congruent picture emerging from fossils, development and molecules BioEssays DOI: 10.1002/bies.201100001

MAZUREK, D., & ZATOŃ, M. (2011). Is Nectocaris pteryx a cephalopod? Lethaia DOI: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.2010.00253.x

Smith, M., & Caron, J. (2010). Primitive soft-bodied cephalopods from the Cambrian Nature, 465 (7297), 469-472 DOI: 10.1038/nature09068

Simonetta, A. (1988). Is Nectocaris pteryx a chordate? Italian Journal of Zoology, 55 (1), 63-68 DOI: 10.1080/11250008809386601

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest