Standing 16 feet tall at the shoulder and weighing 20 tons, Paraceratherium was one of the largest mammals to ever walk the Earth. That may seem pretty puny by dinosaurian standards, but, at the American Museum of Natural History and other institutions that house reconstructions of the 34-23 million year old animal, the hornless rhino towers over every other beast. Only a few extinct elephants have come close to its impressive stature.

As is often the case with the large and fossiliferous, though, it’s too easy to get wrapped up in the nature of the beast and forget the history that assembled the creature before us. University of Manchester historian Chris Manias recounts the tale in a new paper. In the case of Paraceratherium, the great rhino only emerged after years of toil, study, and, most importantly, collaboration between researchers who were independently drawn to the remains of the same giant.

Before the rhino could get a name or start casting shade over museum halls, the titan had to be discovered. The British paleontologist Clive Forster-Cooper had the honor. Curious about fossils regularly found by England’s Indian Geological Survey among the Bugti Hills of Baluchistan, Foster-Cooper organized a 1910-1911 expedition to see the fossils for himself.

The work was more difficult than Forster-Cooper had hoped. In the age of imperial paleontology, he took the traditional route of hiring unskilled local workers who he frequently groused about to his esteemed colleagues elsewhere. Not only were the local Nawab people suspicious of the paleontologist’s true motives – who would be travel all the way out there for old bones? – but Forster-Cooper complained that he had to fire three workers for “idleness and insubordination” and did not trust the remaining three with anything more than rudimentary digging around.

Forster-Cooper took on most of the delicate and technical tasks of hardening and jacketing the fossils himself. He had learned the latest in these techniques from American Museum of Natural History paleontologists Henry Fairfield Osborn and Walter Granger just a few years before, at first among the fossil exposures of Egypt and soon after in New York City. And despite the fact that Forster-Cooper lost some of the fossils – such as a large mammal pelvis that had been “ground to powder” by the herky-jerky gait of pack camels – the tricks he learned from the Americans let him carry back a respectable accumulation of remains back to Britain, including some large bones unlike any seen before. Among the most impressive finds were a lower jaw over two feet long and a thigh bone over three and a half feet high. Now here’s where things get a little tricky.

Forster-Cooper recognized that these large remains had come from rhino-like animals, and were to similar to a genus found nearby called Aceratherium, but it seemed as if they did not belong to the same individual. The lower jaw looked too small to go with the legs, and, since it was ready for publication first, Forster-Cooper used it to coin the name Paraceratherium bugtiense.

The legs and associated vertebrae followed in 1913 under a different name. They must have belonged to a larger, different animal, Forster-Cooper reasoned, and so he named the mammal in honor of one of his New York mentors – Thaumastotherium osborni. Unfortunately for Forster-Cooper, though, that genus name was already pre-occupied by a beetle, and so he promptly changed the moniker to Baluchitherium in honor of the region where he found the bones.

But no one really knew what these mammals were. Forster-Cooper had a hunch that Paraceratherium and Baluchitherium were rhinos, though there wasn’t enough left of either to be entirely certain. Osborn disagreed and suggested that the beasts were Indian versions of one of his favorite groups of mammals – the superficially rhino-like brontotheres – and was so confident that he traded Forster-Cooper some brontothere foot bones for casts of the Baluchitherium material.

What Forster-Cooper and Osborn didn’t know was that the Russian paleontologist Alexei Borissiak had already found more of the same perplexing animal. Geologists working in “Turkestan” had found huge bones that Russia’s Geological Museum of the Imperial Academy of Sciences dug up and sent to Saint Petersburg in 1913. The remains looked like mammoth fossils to the geologists who excavated them, but, after preparing a large thigh bone sent back to the city, Borissiak realized that the animal was no elephant. The bones represented “a totally unknown giant.”

After studying the femur and other pieces – including teeth and forelimbs from eleven individuals – Borissiak came to the same conclusion that Forster-Cooper did. The bones must have belonged to some sort of rhino, or at least a very close relative. Naturally, such a stupendous beast needed a name. Drawing from the Russian folktale The Book of the Dove, Borissiak named the creature Indricotherium.

The trouble was that Borissiak wrote his monographs on the rhino in Russian. English and American paleontologists could not read the Russian journals, Manias writes in his study, and their Russian colleagues only had a sketchy grasp of what English-speaking paleontologists were up to. Forster-Cooper and Osborn only learned about Borissiak’s work in 1920 – four years after the first Indricotherium paper was published – and had to wait another year for translations of the monograph.

Despite the delay caused by World War I and the language barrier, though, Forster-Cooper was elated when he finally got the news. Among Borissiak’s fossils were pieces that Forster-Cooper also had in his haul, and the parts that overlapped seemed to be identical in size and anatomy. Borissiak’s “Indricotherium” looked to be another Baluchitherium, and the new cache of bones provided even more clues that the beast was a huge rhino.

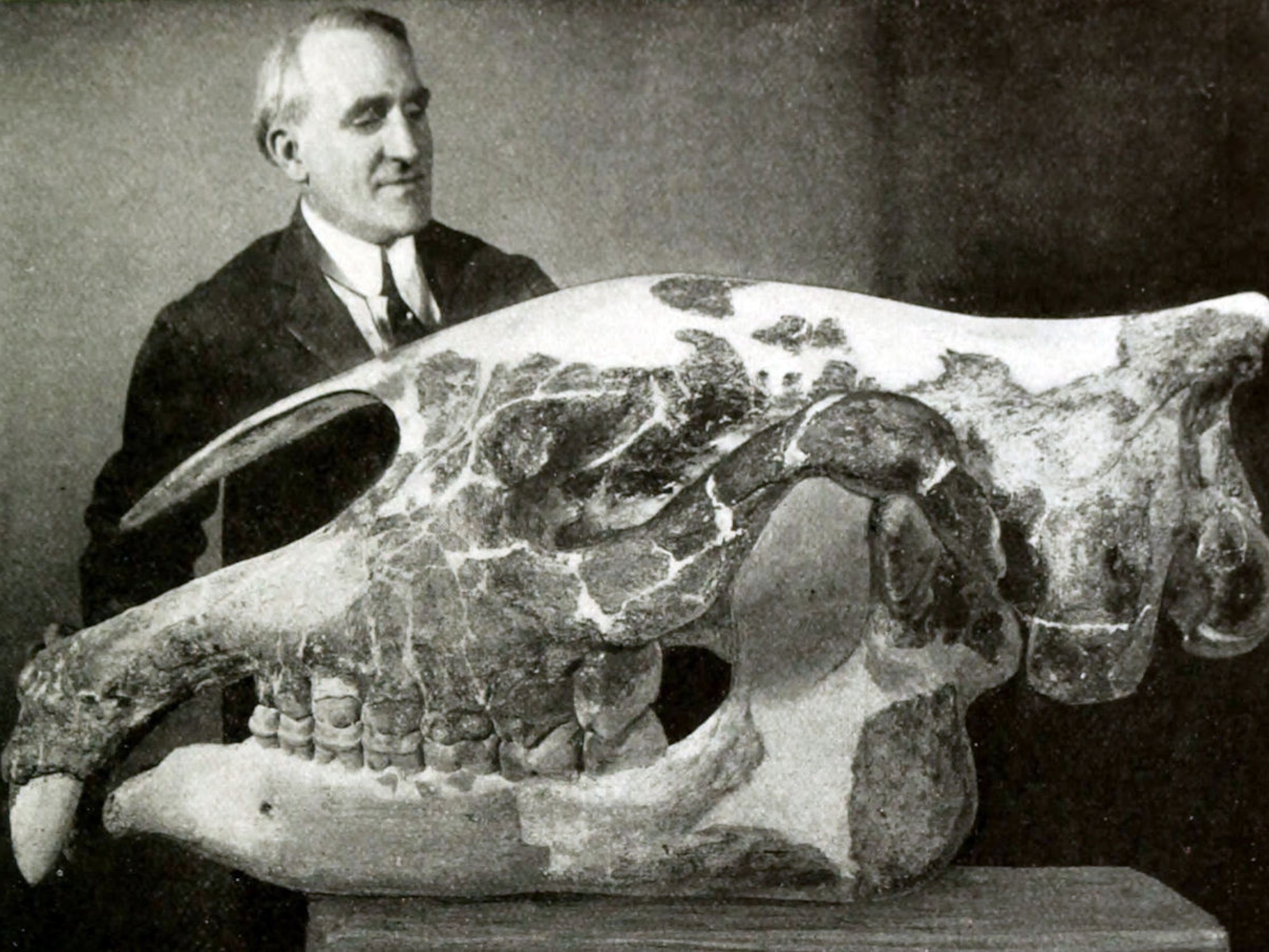

It wasn’t long before the American Museum of Natural History’s 1923 expedition to Mongolia would finally confirm Forster-Cooper’s hunch and put a face on the animal. Following a tip from local people, expedition leader Roy Chapman Andrews led his well-equipped paleontological team to a site where gigantic bones were said to be emerging from the ground. Sure enough, some huge fossil animal met them at the site, and the crew soon found the skull. Osborn was elated when the specimen arrived back in New York, especially since such an exciting find raised hopes that he might have better luck scaring up the ten thousand dollars needed to send the expedition back for more the next season.

Finding the rhino’s skull was a fossil coup. Forster-Cooper and Borissiak had found the first bones, Manias notes in his study, but they lacked the vast workforce and media savvy of the AMNH that – albeit briefly – let a fossil mammal outshine even the biggest dinosaurs in the public imagination. All the same, the AMNH researchers made sure to mention their international colleagues in their reports and sent casts to both England and Russia, with Borissiak sending casts of his “Indricotherium” material to America and England in return. This was not just a matter of fairness, but paleo diplomacy that reinvigorated scientific relations between Russia and the West.

Not that picture was entirely rosy. Even though the names “Baluchitherium” and “Indricotherium” were still being used when I first learned about this animal in the 1980s, paleontologists suspected that Paraceratherium was the proper title since about 1927. Paleontologist William Diller Matthew of the AMNH wrote as much to Borissiak in that year, which spurred no small amount of consternation in his boss. The first “Baluchitherium” species was named after him, after all, not to mention that the AMNH had publicized the hell out of the name. So “Baluchitherium” stuck, and Borissiak preferred to keep “Indricotherium” for his fossils throughout his career, too. Only more recently – long after all who might be offended have passed away – has Paraceratherium stepped to the fore.

Political shifts eventually brought an end to the international cooperation. The AMNH wound up being barred from Mongolia for decades, and the formation of the USSR eventually locked paleontologists within the Soviet Union. Borissiak could still keep in touch with outside scientists – such as sending photos of his “Indricotherium” mount when it was moved to Moscow in 1938 – but travel to meet and collaborate moved from difficult to impossible. Nevertheless, between 1910 and 1930 paleontologists worked together to assemble the largest land mammal ever known. Conflict over fossils more regularly makes headlines – from the “Bone Wars” of the 19th century to arguments over the commercialization of fossils today – but, as Manias argues, the bones of the great rhino stand as testament to scientific collaboration.

Reference:

Manias, C. 2014. Building Baluchitherium and Indricotherium: Imperial and international networks in Early-Twentieth Century paleontologyBuilding Baluchitherium and Indricotherium: Imperial and international networks in Early-Twentieth Century paleontologyBuilding Baluchitherium and Indricotherium: Imperial and international networks in Early-Twentieth Century paleontologyBuilding Baluchitherium and Indricotherium: Imperial and international networks in Early-Twentieth Century paleontologyBuilding Baluchitherium and Indricotherium: Imperial and international networks in Early-Twentieth Century paleontology. Journal of the History of Biology. doi: 10.1007/s1039-014-9395-y

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads