Expanding Guts in Pythons and People

Regular readers of this blog might remember a post I wrote a few months ago about weight-loss surgery. A mouse study suggested that surgery works — triggering weight loss and, often, diabetes remission — not because it makes the stomach smaller, but because it drastically changes its biochemistry.

I took a close look at that study and a slew of others in a feature published in today’s issue of Naturetoday’s issue of Nature. Rodent models have shown that after surgery, the gut goes through many dramatic changes. Bacterial compositions shift, for example, bile acids flow more freely, and the intestines swell.

That last bit maybe isn’t so surprising — after all, once the stomach shrinks to the size of an egg, suddenly a whole lot more undigested food is going to hit the intestines than before. But what is surprising, as Nicholas Stylopoulos’s group published last year in Science, is that this abrupt growth seems to trigger a host of permanent metabolic changes in the gut.

As I explain in the feature:

“The rapid growth requires a lot of energy, which comes from glucose. Glucose uptake by the changing organ increases, and the change is maintained over time, Stylopoulos says. ‘Essentially, the intestine becomes a bigger and a more hungry organ that needs more glucose than before.’

Stylopoulos believes that this tissue growth in the gut is the main driver of the surgery’s remarkable metabolic benefits — not a reduction in calorie intake.”

A couple of weeks ago, while I was doing the final fact-checks for the feature, Stylopoulos told me a fun tidbit about how the same sort of change has been reported in….wait for it….Burmese Pythons. “They have some amazing similarities,” he said.

Unlike most mammals, which eat small meals several times a day, pythons engulf enormous meals — ranging from .25 to 1.6 times their own body mass — many months apart. As biologists Stephen Secor and Jared Diamond pointed out in a 1998 Nature paper1998 Nature paper1998 Nature paper, that would be equivalent to a 136-pound person swallowing a 220-pound meal “in one gulp.”

After it has finished its meal, a python curls up for 5 to 11 days to digest it. “They have this amazing capacity to increase the length and the overall mass of their intestines within hours,” Stylopoulos told me. Once digestion is complete, their gut goes back to normal.

So the python gut expands rapidly after eating, just as Stylopoulos showed happens in the rat gut after bypass surgery. But “what is really amazing,” Stylopoulos said, is that the python gut also sees a surge in glucose metabolism after being fed.

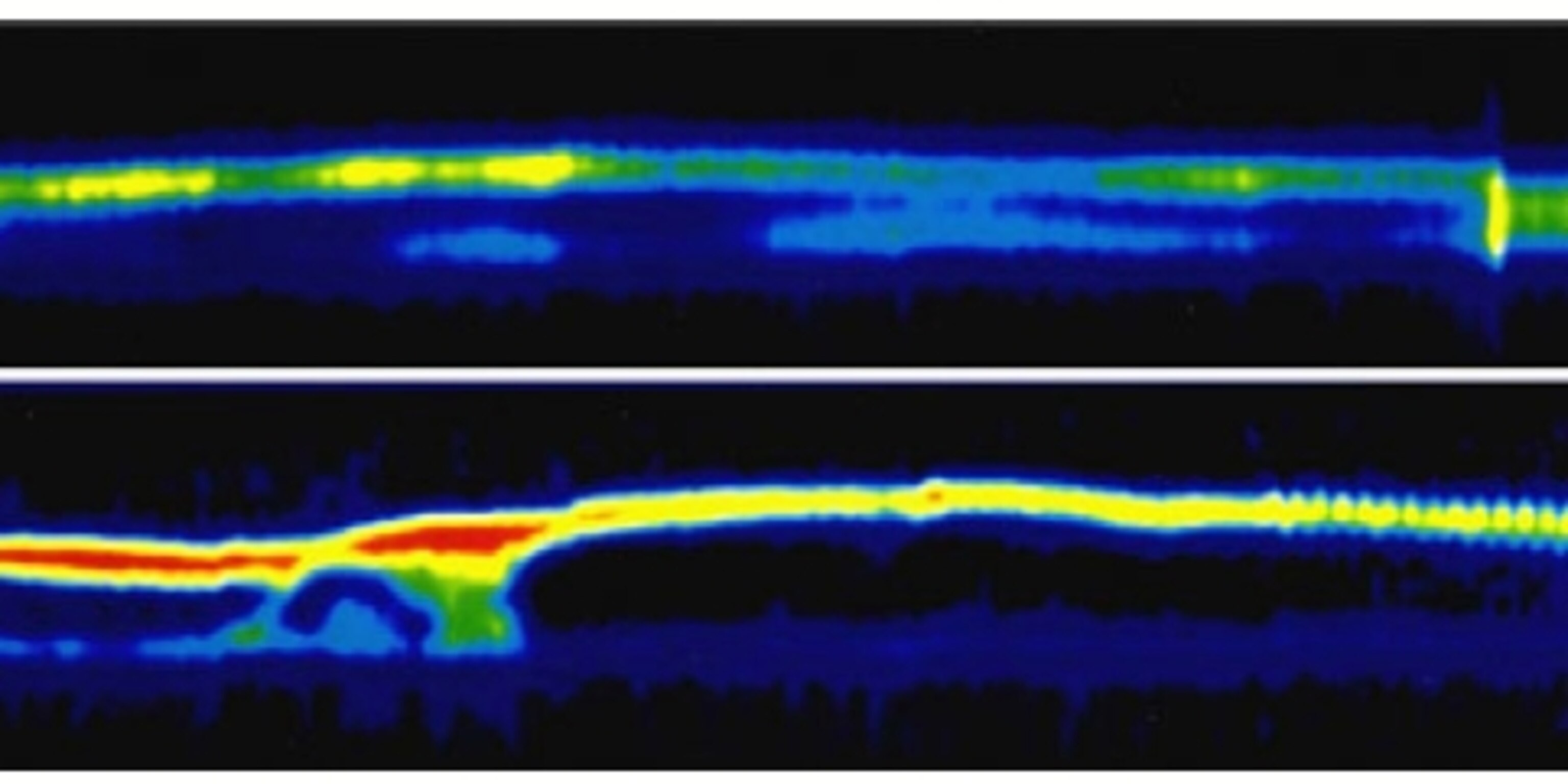

Here’s an image from one of Sekor’s later studies, showing glucose levels (red and yellow) in a hungry animal (top) versus a just-fed one (bottom):

The difference between the python model and the bariatric surgery model is that for pythons, the gut goes back to normal once the food is gone. With surgically treated rats, in contrast, the gut expansion doesn’t seem to go away, presumably because the undigested food keeps on coming.

That said, Stylopoulos’s study found that the post-surgery gut doesn’t grow forever. Over time, it reaches a plateau and so does its glucose metabolism. That could be why some people who see initial metabolic benefits after bariatric surgery ultimately regress back into diabetes.

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads