Can You Tell a Woman by Her Handprint?

Edit, 12/14, 10:59pm: This post has now been updated with responses from the new study’s lead author.

A few months ago I wrote a story for National Geographic Newsstory for National Geographic Newsstory for National Geographic Newsstory for National Geographic News that seemed to pique a lot of readers’ imaginations, and understandably so. It was about a study by Dean Snow reporting that, contrary to decades of archaeological dogma, many of the first artists were women.

Neat, right? But now there’s a twist in the tale: Another group of researchers is claiming the study’s methods were unsound. Snow has his own critiques of the criticism (more on that later). I’m less interested in who’s right than a fundamental question behind the controversy, and one that is relevant to all archaeological investigations: What does the present have to do with the past?

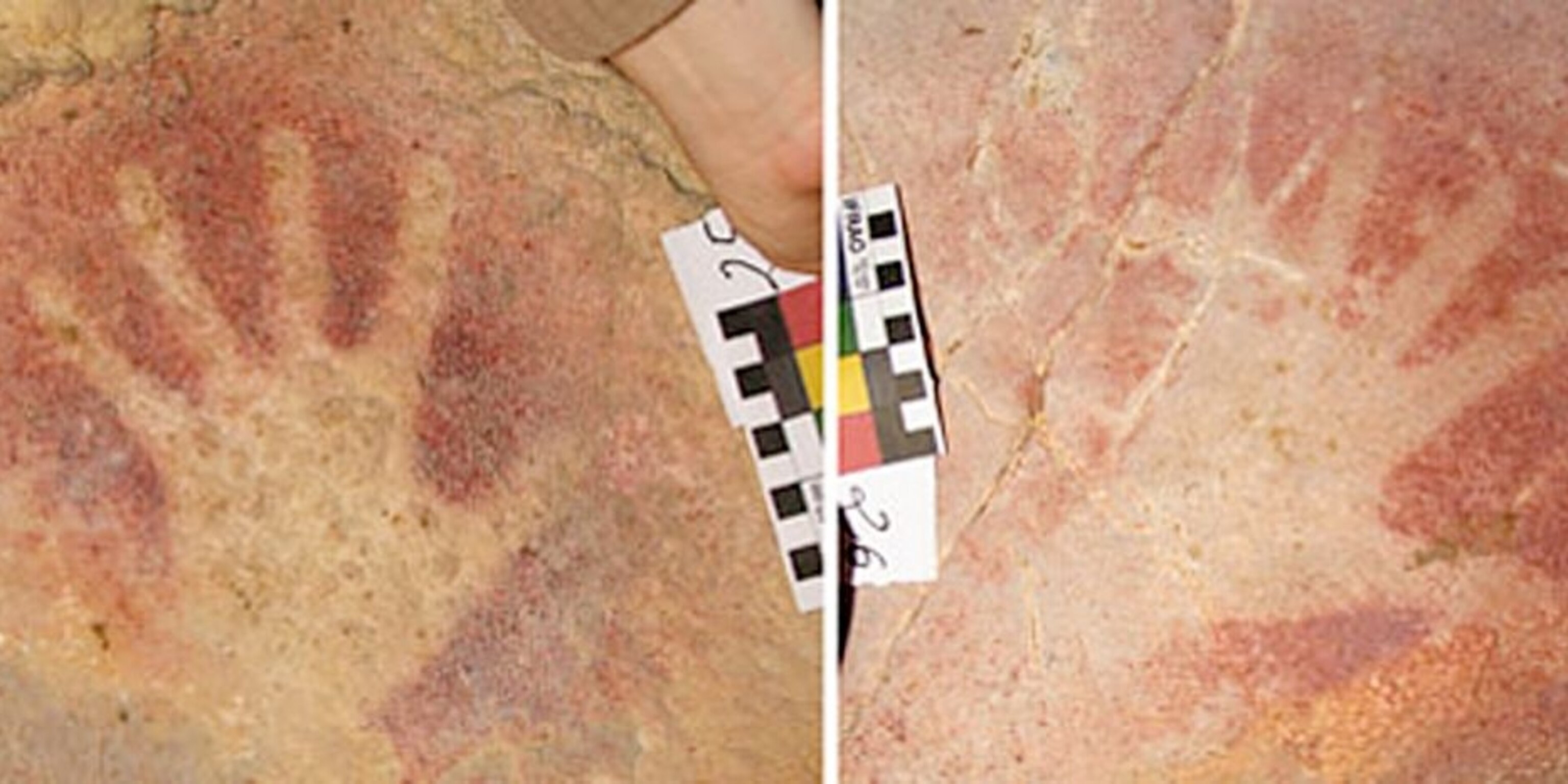

Snow’s study, published in the journal American Antiquity last October, focused on the famous 12,000- to 40,000-year-old handprints found on cave walls in France and Spain. Because these hands generally appear near pictures of bison and other big game, scholars had long believed that the art was made by male hunters. Snow tested that notion by comparing the relative lengths of fingers in the handprints. Why? Because among modern people, women tend to have ring and index fingers of about the same length, whereas men’s ring fingers tend to be longer than their index fingers.

Snow first scanned the hands of 111 people of European descent who lived near Pennsylvania State University, where he is an emeritus professor of anthropology. By comparing male and female hands on specific measures — such as the length of the fingers, the length of the hand, the ratio of ring to index finger, and the ratio of index finger to little finger — Snow developed an algorithm that could predict the sex of a given handprint. He also validated the algorithm on a second set of modern hands (50 males and 50 females).

The algorithm was only weakly predictive — with an accuracy of just 60 percent — because there’s a lot of overlap between the hands of modern men and women. But the equations were far more accurate when used on a set of 32 ancient hand stencils. The various measurements of these hands fell at the extreme ends of the modern sample, making it easy for the algorithm to categorize them as male or female. Snow found that 24 of the 32 prints — 75 percent — were female.

The new study, published Monday in the Journal of Archaeological Science, challenges Snow’s reference sample. A team led by Patrik Galeta of the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen, Czech Republic, collected handprints from 100 contemporary people in southern France and then ran those measurements through Snow’s algorithm.

Galeta found that Snow’s algorithm predicted female hands fairly well, but was useless for males, making it overall a bad predictor of sex. The study showed, in other words, that sex differences in hands among modern people living in Pennsylvania are not the same as differences among modern people living in France. “Our understanding is that hands of French males are on average smaller than U.S. males,” Galeta notes. And that, he adds, “is why U.S. methods failed to correctly identify French males.”

The bottom line: if two modern populations don’t match, then how can we possibly say anything about handprints tens of thousands of years old?

“What this shows is that a basic assumption that everyone has been making is wrong, which is that we can take a contemporary human population and use it as a model across space and time,” says archaeologist David Whitley of ASM Affiliates, an archaeological consulting firm in Tehachapi, California. Whitley was not involved in either study.

This might explain, Whitley adds, why researchers studying these old handprints have often come to contradictory conclusions. Before Snow’s work, evolutionary biologist R. Dale Guthrie performed a similar analysis of the cave prints and reported that most of them came from adolescent boys.

Snow, however, doesn’t agree with the criticisms of the new study. “I would stand by my guns here,” he says.

He sees two possible reasons that his algorithm didn’t work on the new French sample. One is that the Czech researchers didn’t use his algorithm in the same way that he did. Snow did his analysis in two steps, running the data first through an equation related to the length of the hand, and then running those results through another equation based on the ratio between the index and ring finger. The Czech researchers, in contrast, looked at the two equations separately.

Alternatively, it could be that the Czech researchers didn’t measure hand length the same way Snow did, he says. Snow measured from the tip of the middle finger to the creases where the wrist meets the palm. “If you measured the length of the hand using some other terminus at the base, you might lose a centimeter or so of the overall length,” Snow says.

So who’s right, and how can this be resolved? “I would have to see their data, and they would have to see my data, and we would have to work it out,” Snow says.

So far neither group has made contact with the other, though both parties seem willing. and the Czech group has not yet responded to my queries about their work. (If and when they do I’ll be sure to update this post.) The Czech group, for the record, rejects both of the explanations Snow proposed, saying that they used the algorithm and measured the hands exactly as Snow did.

Even if the Czech group is right, Snow says the main conclusion doesn’t change. “Even with their sample, they can show as well as I can that there were some women in them caves,” he says. “They might argue, well was it 50-50 or 70-30 or 80-20, but that part of it doesn’t concern me so much.”

Experts have been arguing over the identity of these handprints for decades, and that debate isn’t going away anytime soon. That’s part of good science. But I think this story also says something interesting about archaeology.

Archaeologists are constantly turning up objects from the distant past, and their job is to figure out what (or, in this case, who) they were. They begin, naturally, by making assumptions based on the objects and people we’re familiar with today. “It’s an issue we always confront — making ‘presentist’ projections onto the past,” Whitley says.

In the case of these handprints, the projection relates to our bodies. But it could be anything. “If you find a pot, then just calling it a pot assumes you have some understanding of what it was,” Snow says. “We all make inferences. You just have to be reasonably comfortable with your inferences.”

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads