Who doesn’t dream of finding a dinosaur? There are no prehistoric creatures quite so cherished, and stumbling across their fossilized remains is always a joyous occasion. And pride in uncovering such petrified pieces doesn’t belong to professional paleontologists alone. In 2009, high school student Kevin Terris spotted what experts had missed – bones that led the way to the stunningly-complete skeleton of a baby hadrosaur.

Terris, then a student at Claremont, California’s Webb Schools, spotted bits of bone poking out of roughly 75 million year old rock in southern Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Experts had recently passed by the same spot and missed the clues. A sharp eye and luck are still the most essential tools for dinosaur hunters.

The site Terris found fell within the Kaiparowits Formation – a record of a Cretaceous dinosaurian Eden. Today this arid stretch of the Colorado Plateau is covered by cracked juniper and sagebrush, but during the time the little dinosaur lived – and perished – this area was a lush swamp not so very far from a long-vanished seaway that split North America in two.

Finding bone in the Kaiparowits Formation isn’t especially hard. Bits of turtle shell and damaged pieces of dinosaur bone are everywhere. But Terris had made a truly spectacular find. After excavation and preparation in the lab, it became clear that Terris had found a remarkably complete skeleton. These dinosaurs were shovel-beaked herbivores equipped with dense batteries of teeth for cutting and grinding the vegetation they spent their days scoffing down. But what species of hadrosaur was it?

Baby hadrosaurs can be very frustrating fossils. If found without skulls, as often happens, the rest of their skeletons don’t always contain the tell-tale traits that allow paleontologists to narrow down their specific identity. And even with skulls, baby hadrosaurs changed so dramatically as they grew up that young individuals have sometimes been confused for different species. During the early 20th century, paleontologists thought they had found multiple species of a tiny hadrosaur they called Prochenosaurus, only to have later researchers figure out that all these specimens were actually the young of already-named, ornately-crested species. Terris’ hadrosaur – nicknamed “Joe” – presented a similar puzzle.

In a paper published today in PeerJ, Joe’s identity has finally been revealed. The young dinosaur was a little Parasaurolophus – a beautifully-crested herbivore thought to have used its cranial ornaments to make low, booming calls across the Cretaceous landscape. This makes Joe the most complete member of this dinosaur yet known. Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology curator Andrew Farke, Webb Schools students Derek Chok, Annisa Herrero, and Brandon Scolieri, and Stony Brook University histology expert Sarah Werning worked together to figure out who Joe was and how the immature dinosaur lived.

Skull features that take an anatomist’s eye to see pinned down Joe as a little Parasaurolophus. A straight edge along one of the jaw bones and the fact that the nasal passages entirely fill Joe’s little bump of a crest are a better fit for Parasaurolophus than any other hadrosaur. The fact that scrappier skeletons of adult Parasaurolophus have been found in the same formation help solidify the case for Joe’s identity. And even though Joe didn’t look just like those adults, the young dinosaur was still quite flashy.

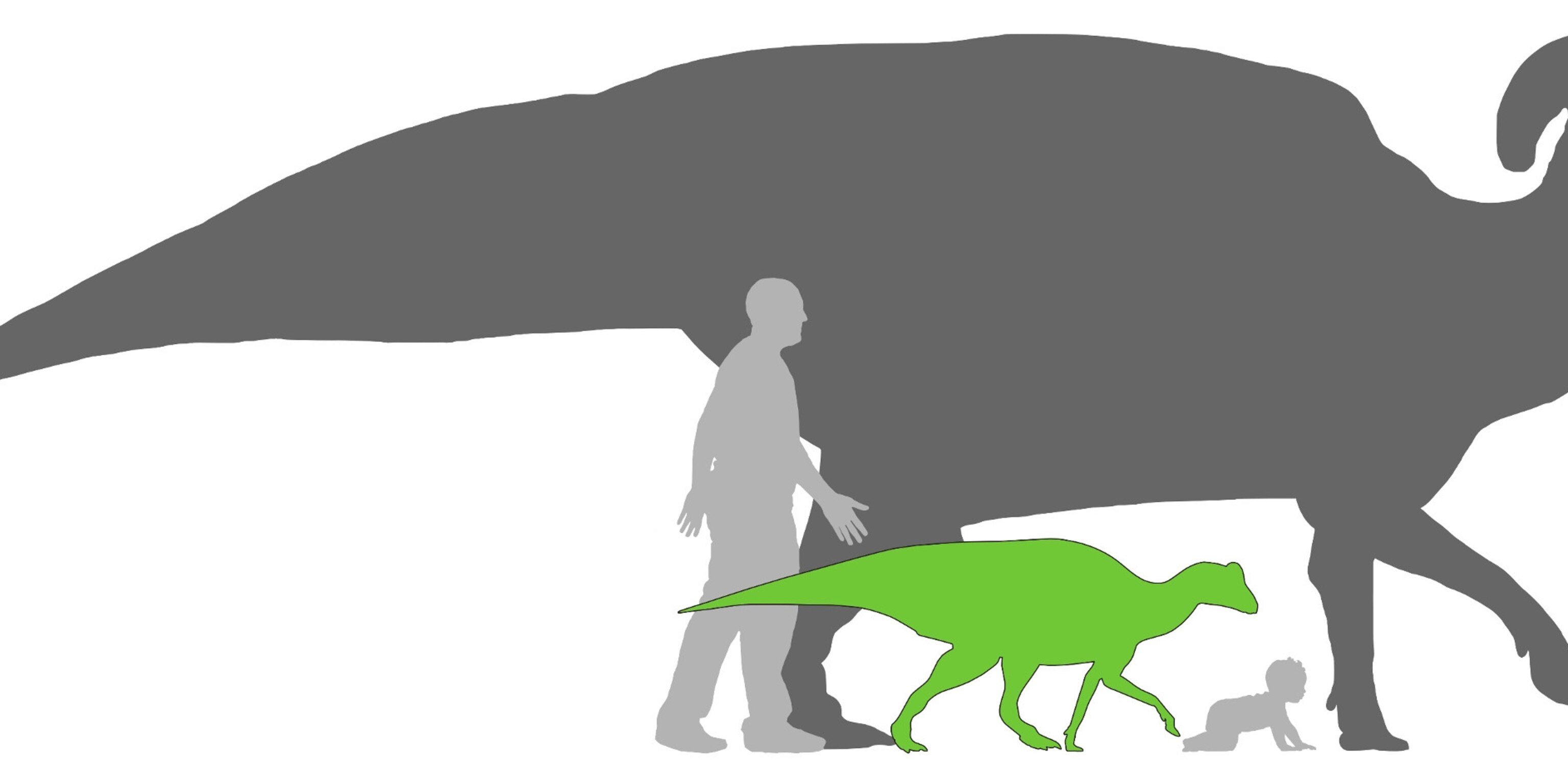

At death, Joe was only about a quarter of adult size. Yet Joe was already developing a prominent crest. This is early compared to other crested hadrosaurs that didn’t start growing bizarre ornaments until they were about half of their adult size. Exactly how old Joe was at death is still unclear – perhaps less than a year, perhaps a bit older than that – but the size of the dinosaur, the development of its crest, and the microscopic structure of the animal’s bones all indicate that this was a young, fast growing hadrosaur. Joe may have gone from being a hatchling you could have held in your hands to an eight-foot-long dinosaur in less than a year – a truly astonishing growth rate.

And there’s more to Joe than just bones. Like other hadrosaurs found in the Kaiparowits Formation, patches of skin impressions surrounded the little dinosaur’s skeleton. Even better, the stone around Joe’s skull preserved part of the tough beak. Even though these dinosaurs are often called “duckbills”, fossils such as Joe show that they were more shovel-beaked. And from that beaked mouth, Joe probably squeaked.

From the crests and inner ears of adult Parasaurolophus, paleontologist David Weishampel previously figured out that these dinosaurs could have made low-frequency calls that probably traveled far and wide through Cretaceous wetlands. Joe didn’t yet have such a prominent crest, but, using the same principles, Farke and coauthors estimated that the young Parasaurolophus made calls at frequencies 11 to 18 times higher than that of adults. As the appearance of these dinosaurs changed with age, their voices changed, too.

And to think that Joe could have been easily missed. There are more dinosaurs hiding just under the surface than we’ll ever know. Of all the dinosaurs that ever lived, a fraction became preserved as fossils, and an even tinier portion will ever be found. But every single skeleton, every single bone or tooth, is a time capsule that still contains traces of life that we can sadly never witness firsthand. That we can understand Joe’s life in such detail is a testament to how much the fossil record can tell us, and how much we may yet learn about lost worlds.

Reference:

Farke, A., Chok, D., Herrero, A., Scolieri, B., Werning, S. 2013. Ontogeny in the tube-created dinosaur Parasaurolophus (Hadrosauridae) and heterochrony in hadrosauridsOntogeny in the tube-created dinosaur Parasaurolophus (Hadrosauridae) and heterochrony in hadrosauridsOntogeny in the tube-created dinosaur Parasaurolophus (Hadrosauridae) and heterochrony in hadrosaurids. PeerJ. 1: e182. http://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.182

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park