Imagine – by an unforeseen temporal slip or a time machine accident – that you find yourself in western Canada, circa 75 million years ago. You might need a few moments to realize that something has gone horribly wrong. Between towering stands of sequoia just sparse enough to let the sun shift on the forest floor, swaths of ferns and small herbs cover the ground, interrupted here and there by mulberry-like shrubs. Watching a dinosaur amble out of the forest onto the carpet of greenery would probably be your first clue that something had gone awfully wrong.

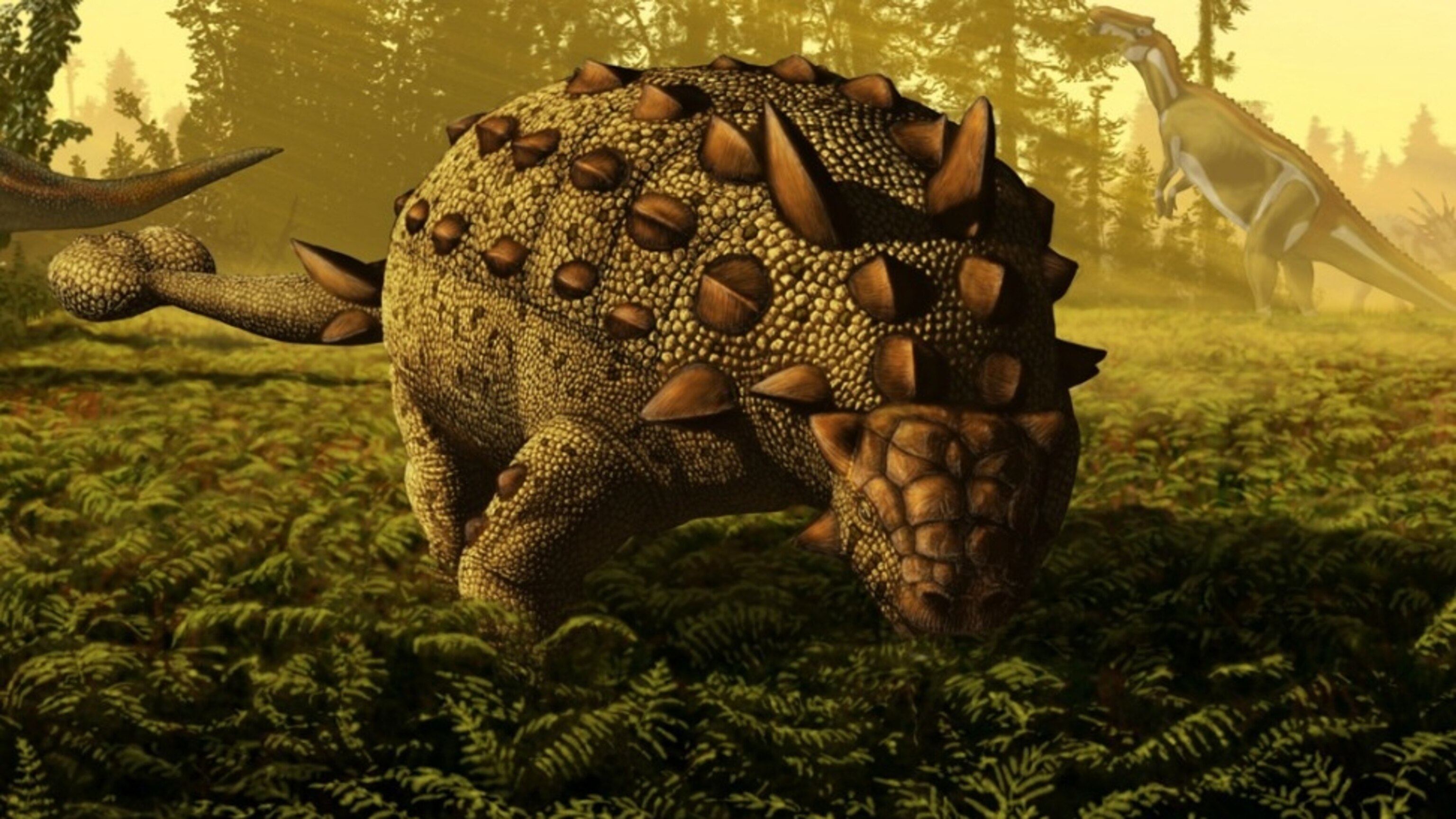

By virtue of their numbers, chances are that you’d spot a megaherbivore first. (Or at least you’d hope – out in the open, you’d stand little chance against the tyrannical Gorgosaurus.) The dinosaur might be one of the armor-wrapped ankylosaurs, a beak-faced ceratopsid with a frill adorned with beautifully-imposing horns, or a graceful hadrosaurid that stares at you sideways out of a shovel-beaked skull. During this time – scattered remnants of which are preserved in Alberta’s Dinosaur Park Formation – the landscape hosted great communities of disparate, foliage-plowing giants. And if you weren’t occupied with the pressing questions of finding cover and getting home, you might wonder how so many multi-ton, plant-pulverizing titans managed to coexist with one another.

From top to bottom, the Dinosaur Park Formation is a 1.5 million year chunk of Cretaceous time. Within that petrified slice, paleontologists have exhumed at least three species of the armored ankylosaurs, six species of the horned ceratopsids, and eight species of the shovel-beaked hadrosaurs, bringing the total to seventeen hulking herbivores. These dinosaurs didn’t all live alongside one other.

The prehistoric tenants of the Dinosaur Park Formation change as you look through the section, and some of the species – such as the tube-crested hadrosaurid Parasaurolophus walkeri – are rare creatures that apparently wandered through the area from time to time or just never achieved the numbers of their neighbors. Still, the Cretaceous habitats of the Dinosaur Park Formation hosted roughly six different species of megaherbivores with representatives from the ankylosaur, ceratopsid, and hadrosaurid groups at any one time. How was this possible?

Paleontologists have considered two main hypotheses to explain the Cretaceous communities. Perhaps, some researchers have argued, such ancient habitats were so overabundant with vegetation that there was food for all. Or, as a corollary to this, maybe dinosaur metabolic rates were so sluggish that each individual animal could persist on less and therefore avoid competition for food. But a new PLoS One study by University of Calgary researchers Jordan Mallon and Jason Anderson throws support to an alternative notion. To a greater or lesser degree, each dinosaur species might have had anatomical specializations for particular kinds of plants – a varied aggregation of dinosaur grazers and browsers with each species preferentially targeting different plants from the buffet.

Niche partitioning makes good neighbors. An ecosystem where herbivores have been adapted to specialize on particular foodstuffs will typically support a greater variety of species than a community where generalists are all picking from the same sources of nourishment. To investigate the possibility of ecological divisions in the Dinosaur Park Formation, Mallon and Anderson looked to measurements of herbivorous dinosaur skulls.

Based on observations of modern animals, zoologists and paleontologists have discerned that there are peculiar anatomical conditions associated with different ways of feeding. Grazers that scoff low-lying swaths of plants often have squared-off muzzles to let them get their mouths close to the ground, while browsers that more carefully select leaves and branches typically have more rounded or pointed snouts. Features such as the extent of the tooth row along the jaw and the width of parts of the skull can also yield suggestive clues. Mallon and Anderson selected twelve of these measurements from Dinosaur Park Formation herbivores to see how the likes of the spiky-frilled Styracosaurus, the dome-crested Corythosaurus, and osteoderm-encased Euoplocephalus compared in terms of their feeding abilities.

The skulls of ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids are drastically different on sight, and, as Mallon and Anderson confirmed, each group had a different set of feeding abilities. The ankylosaurs had wide, flat-snouted skulls with short rows of teeth. This might be taken as evidence of a relatively weak bite, the researchers noted, but other anatomical landmarks – such as expanded space for jaw muscles – hint that ankylosaurs might have been feeding on relatively tough food that sprouted low to the ground.

Ceratopsids such as Chasmosaurus and Centrosaurus had huge, drastically different skulls. Behind their pointed beaks, these dinosaurs had an elongated tooth row and space for a powerful chewing apparatus. The horned dinosaurs, Mallon and Anderson propose, were choosy browsers that plucked soft herbs when possible but relied upon tough, woody vegetation that was a little bit above the heads of ankylosaurs.

The hadrosaurs apparently had a wider menu to choose from. Dinosaurs such as Lambeosaurus and Gryposaurus were capable of strutting on two legs as well as four, allowing them to shear low-lying plants as well as reach high for leaves and bark. A more generalist diet might explain why their skulls seem to show adaptations for both grazing and browsing – an extended battery of teeth to pulverize resistant browse, but a squared-off beak for cropping plants along the floodplain floor.

Some of these groups even showed differences between their subdivisions. Among the ankylosaurs, there are two subsets represented in the Dinosaur Park Formation – the ankylosaurids and the nodosaurids. The main ways to tell these groups apart is by their armor, but Mallon and Anderson found that they also differed in the anatomy of their lower jaws – the nodosaurids seemed capable of handling tougher food. Then again, there seemed to be no such distinction between the feeding anatomy of the two ceratopsid groups – the centrosaurines and chasmosaurines – while the hadrosaurid subgroups were mostly distinguishable by skull size. The more closely-related the species, the less they differed.

Ankylosaurs grazed low, ceratopsids browsed in the middle, and the hadrosaurids took advantage of foliage at all levels. These divisions, Mallon and Anderson argue, explain how communities of so many megaherbivores were able to persist for 1.5 million years. Individual species evolved and succumbed to extinction, yet the ecological divisions between the three sorts of dinosaur persisted through time. The sight of such enormous grazers and browsers pruning back the Mesozoic garden must have been one of the most spectacular sights in the entire history of life on Earth.

Reference:

Mallon, J., Anderson, J. 2013. Skull ecomorphology of megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. PLoS One. 8, 7: e67182

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads