Nearly two centuries ago, naturalists made crocodiles and tortoises walk over soft pie crust for science. The flour-dusted experiment was an attempt to capture the movement of an animal that had been dead for an incomprehensible amount of time.

The inspiration for the experiment, organized by Oxford University naturalist William Buckland one day in 1824, was a fossil trackway that had been discovered in the prehistoric sandstone of Corncockle Muir in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. The ancient, multi-toed, vaguely hand-shaped imprints had caught the attention of a Mr. Carruthers, who extricated the fossils and presented them to the Church of Scotland minister Henry Duncan. The reverend used the tracks to decorate his summerhouse, but he also created casts which he sent along to Buckland.

What sort of creature could have made the tracks? The answer wasn’t immediately clear. Discovered in what British geologists called the New Red Sandstone, the tracks came from an age slightly earlier than the great prehistoric reptiles – soon named Megalosaurus and Iguanodon – that had been found elsewhere. Still, as far as early 19th century geologists were concerned, Duncan’s tracks were laid down during a time when reptiles ruled, so it was only natural to turn to modern reptiles for clues about what sort of animal created the traces.

In the company of colleagues, Buckland somehow persuaded a small crocodile and three tortoises to walk across clay, sand, and soft piecrust to see if he could recreate the footprints on Duncan’s slab. (Sadly, there don’t appear to be any detailed notes about the trials.) John Murray, the man who would eventually publish Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, was in attendance, and later described the event in a letter to a friend:

It was really a glorious sight to behold all the philosophers, flour-besmeared, working away with tucked-up sleeves. Their exertions, I am happy to say, were at length crowned with success; a proper consistency of paste was attained, and the animals walked over the course in a very satisfactory manner; insomuch that many who came to scoff returned rather better disposed towards believing.

The crocodile’s tracks were a poor match for the prehistoric traces, but Buckland came away convinced that the tortoises had created close matches to the fossils. The hoary chelonians that left the impressions would have been a little quicker and lively than their modern counterparts, Buckland concluded, but the tracks affirmed the long tenure of the shelled reptiles on Earth.

Other researchers found similar tracks elsewhere. In 1834, an additional set was found in the Triassic rock of Germany. The imprints recalled “a large man’s hand in a thick fur glove.” German paleontologist Johann Jakob Kaup drew on this superficial resemblance to speculate that the tracks had been left by “an enormous marsupial with thumbs on the rear and front feet.” While the animal’s body was nowhere to be seen, Kaup proposed that the responsible creature be called Chirotherium, the “hand beast” (although Kaup hedged by saying the genus should be “Chirosaurus” should the trackmaker turn out to be an amphibian – a more likely possibility since no one had found any trace of mammals in the same strata).

Kaup’s proposal was hardly the last word. Naturalists debated whether the Chirotherium tracks were made by reptiles, amphibians, or some especially early form of mammal, while non-scientists spun modern folktales about the stone traces being the hand prints of sinners that had died in the biblical Flood. Then, eight years after Kaup gave the tracks a name, the British anatomist Richard Owen hypothesized that he had finally resolved the identity of the mysterious animal. Citing a single tooth found in Triassic rock – a dental fragment with folded enamel which Owen assigned to a group of large amphibians he called labyrinthodonts – Owen proposed that the Chirotherium tracks had been made by something akin to an archaic frog or salamander.

Artists gave Owen’s proposal a terrifying life of its own. Victorian era illustrations of Chirotherium depict nightmarish frogs with crocodile skulls – a kind of otherworldly fairytale beast that parents could have used to scare their children into good behavior. (“Don’t pick your nose or the Chirotherium will get you!”) The creature’s proposed way of walking made it even more fantastic. Even though large Chirotherium tracks looked like hands, the thumbs were wrong. The equivalents of the right hand always showed up on the left side, and the left “hand” on the right. To leave such tracks, geologists such as Charles Lyell speculated, Chirotherium must have walked in a bizarre, criss-cross way to leave these impressions on the wrong sides.

As Victorian paleontologists continued to collect, analyze, and rearrange prehistoric faunas, though, Owen’s proposal began to crumble. Chirotherium tracks were found in Triassic rock, while the heyday of the labyrinthodonts peaked earlier in time. A large, reptilian trackmaker was looking more likely, although the skeletal embodiment of the culprit remained elusive. Unless an animal literally dies in its tracks – a rare, but not unheard of, occurrence – it’s a frustrating challenge matching trace fossil to trace maker.

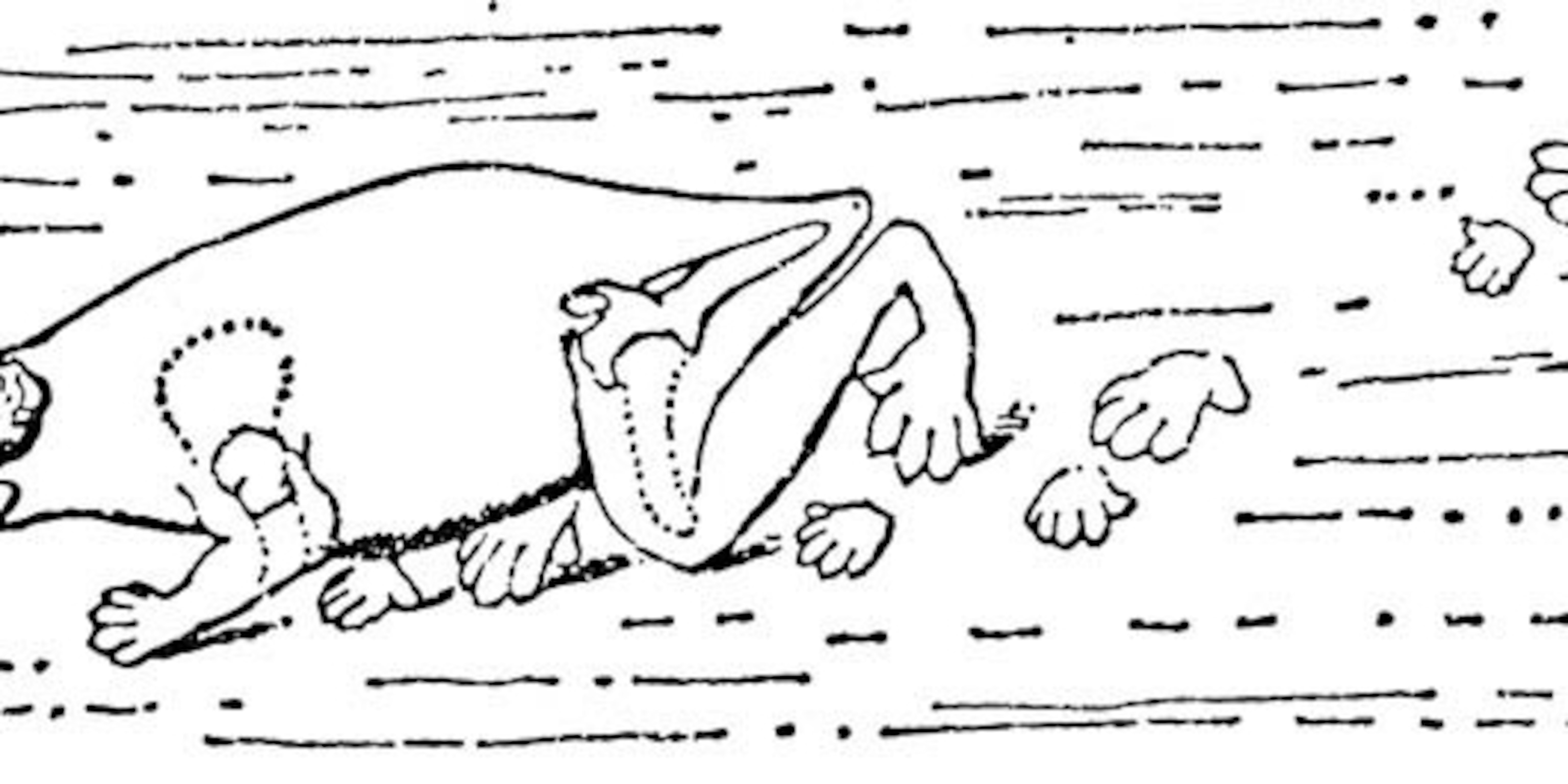

It was only in 1925, a century after Buckland’s doughy experimentation, that the true nature of Chirotherium started to come into view. The German paleontologist Wolfgang Soergel ascertained that previous researchers had been misled by the hand-like appearance of the tracks. The “thumb” was an enlarged, modified toe that truly did belong on the outside of the foot. Whatever made the Chirotherium tracks didn’t have to cross its legs as it walked. This obvious anatomical quirk matched the skeletal structure of pseudosuchians – the varied group of archosaurs that encompasses crocodylians and their extinct relatives.

Soergel illustrated a new, speculative rendition of what the Chirotherium trackmaker must have looked like. The hypothetical critter carried its legs close to the midline of its body, in column-like fashion, and had more robust hindlimbs than forelimbs. Other experts agreed that Soergel’s restoration was probably more accurate than the previous demon-toad illustrations, but it wasn’t until 1965 that a body fossil would test the hypothesis. In that year, paleontologist Bernard Krebs described the skeleton of a large pseudosuchian found in the roughly 240 million year old Triassic rock of Switzerland. Krebs called the animal Ticinosuchus, and its reconstructed skeleton closely resembled what Soergel had proposed on the basis of footprints and general pseudosuchian anatomy. In terms of what we know now, Chirotherium tracks are thought to represent a particular line of pseudosuchians called rauisuchids – deep-skulled, predatory croc cousins with an erect posture. Postosuchus, which may have even walked on two legs rather than all fours, was one such carnivore.

(And while the inference is a stretch by paleobiological standards, paleontologist William Elgin Swinton once commented that the trackways of these pseudosuchians often record short, straight walks without sign of dally or delay. “The reptiles are intent on their journey or their business,” Swinton wrote, pointing out that “They do not loiter but carry on in a straight line” – a charming vision of pseudosuchians intent on their goals.)

But Chirotherium is not the title of an actual animal. Chirotherium is the name of a particular variety of footprint – the trace itself, not the organism. Such tracks have been found across Europe, from England to Italy, as well as in the Triassic rocks of the United States and Argentina. Prehistoric geography makes sense of the pattern. During the Triassic reign of the pseudosuchians, the world’s continents were still locked together in Pangaea. During this time, various genera and species of these distant crocodile relatives left Chirotherium tracks as they stalked through Triassic deserts and over prehistoric lakeshores, their imprints left to us as clues of a spectacular evolutionary chapter before dinosaurs came to dominate the world.

[I also wrote about the odd history of Chirotherium in my 2010 post “When Pseudo-Crocs Walked Tall.”]

References:

Baird, D. 1954. Chirotherium lulli, a pseudosuchian reptile from New Jersey. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. 111, 4: 165-192

Bowden, A., Tresise, G., Simkiss, W. 2010. Chirotherium, the Liverpool footprint hunters and their interpretation of the Middle Trias environmentChirotherium, the Liverpool footprint hunters and their interpretation of the Middle Trias environment, in Moody, R., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D., and Martill, D. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 343, 209–228.

Swinton, W. 1961. The history of ChirotheriumThe history of Chirotherium. Geological Journal. 2, 3: 443-473

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction