A New Culprit in China’s Tainted Milk Saga: Gut Bacteria

Wei Jia became a professor at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in August of 2008, after 10 years working at the Shanghai Jiao Tong University. He is a specialist in metabolomics, meaning that he looks at the chemical byproducts, or metabolites, of cells, tissues and living things. He’s done chemical analyses of the blood of colorectal cancer patients, for example, and of the amniotic fluid of malnourished pregnant rats.

Just a month after Jia moved to the U.S., he and the rest of the world heard about a tragedy in his native country. Thousands of babies in China were sick with kidney stones and several had died after drinking formula laced with a ubiquitous and cheap industrial chemical called melamine.

This was no accident, nor the result of naive incompetence. Dairy companies — nearly two dozen of them — had intentionally added melamine to the milk powder. The manufacturers knew melamine would artificially boost the protein content of the formula, even though the chemical can’t be digested. They thought it was harmless. And they were horribly wrong. Over the next few months, 300,000 children got sick and six died.

As soon as Jia found out, he called his old team of collaborators in Shanghai to start investigating this scientific head-scratcher: Why was melamine so toxic? “Because it’s not, really. It’s not supposed to be absorbable by the human body,” Jia says. Its LD-50 (“lethal dose-50”), or the dose at which 50 percent of those exposed would die, is 3161 mg/kg in rats, an incredibly low toxicity. So why had so many children gotten sick?

Jia’s team turned to studies done on melamine poisoning in pets, research triggered by another Chinese food scandal. Manufacturers in China had long been adding grain containing ground-up melamine to pet food and other animal feed as a cheap filler, and these products were sold in the United States and elsewhere. This came to light in Asia in 2004 and in the U.S. in 2007, when melamine killed 16 dogs and cats in the U.S. and made thousands of others sick. Some 60 million packages of pet food were recalled.

Scientists from the University of Georgia analyzed blood and tissue samples from cats and dogs that had died from the contaminated food. Kidney tissue from all of the animals contained not only melamine, but a chemical called cyanuric acid, which is a common by-product in the manufacturing of melamine, the study found. Jia’s team reported similar results in 2009. They gave rats melamine, cyanuric acid, or a mix of both, and found that tiny doses of melamine could lead to kidney failure, but only when paired with cyanuric acid. It turns out that together, melamine and cyanuric acid form crystals in the kidney that turn into dangerous kidney stones.

According to Jia, many researchers had assumed that the cyanuric acid had come from the pet food, just like melamine. But he suspected otherwise. He knew that in the environment, soil microbes in the Klebsiella family could interact with melamine to produce cyanuric acid. What if the same thing was happening in the gut of the sick pets and babies?

His rat study had shown that when the animals were given high doses of melamine alone, their urine contained a chemical signature — low phenylacetylglycine paired with high trimethylamine-N-oxide and 3-phenylpropionate, for the metabolomic geeks out there — that pointed to the metabolism of gut microbes. But that didn’t prove that microbes had anything to do with the poisoning.

In a new study, published today in Science Translational Medicine, Jia presents much stronger evidence for the idea that gut bacteria spur melamine to make cyanuric acid, leading to trouble.

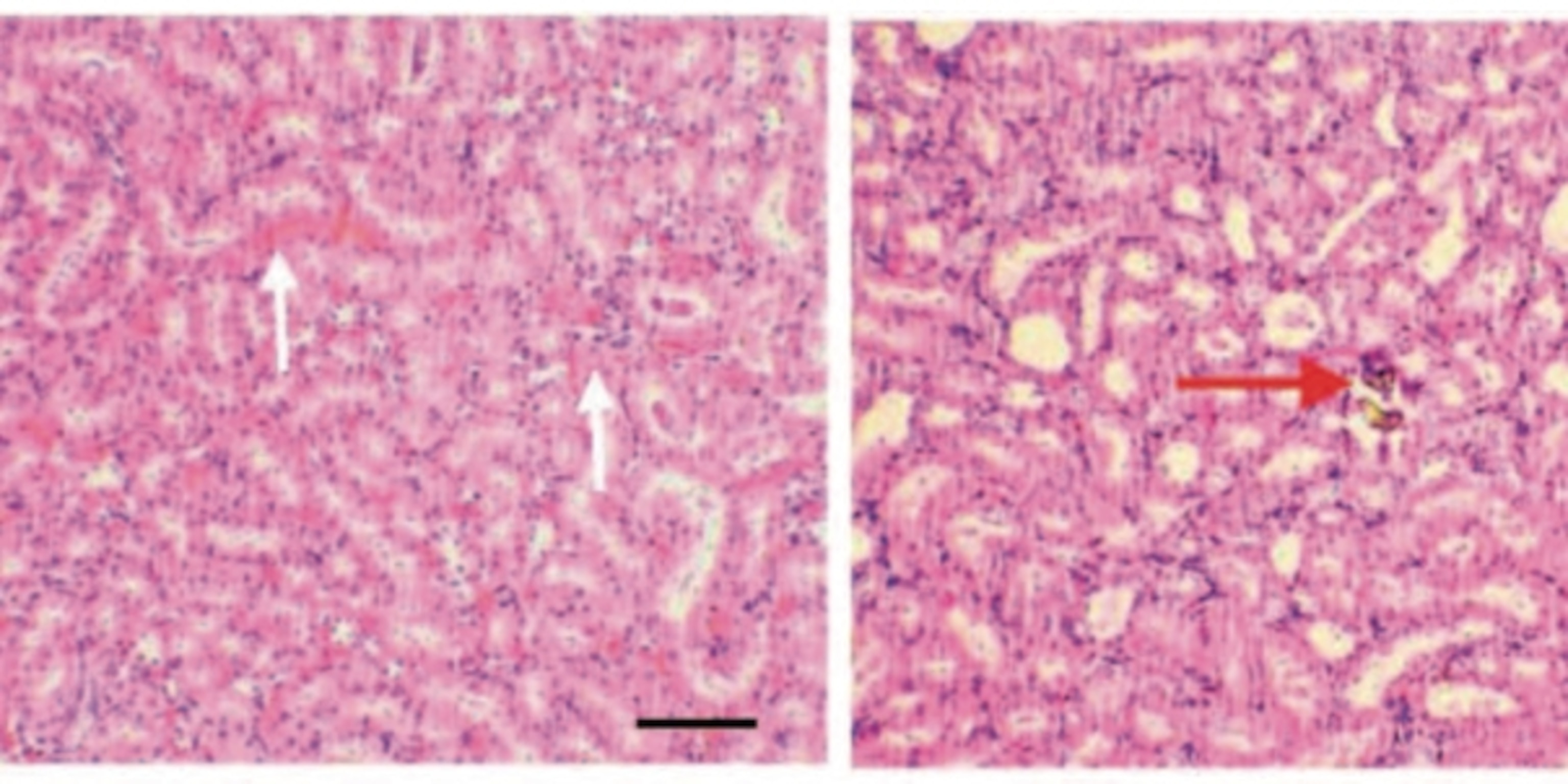

The researchers first gave rats high doses of melamine paired with an antibiotic. The figure below shows the animals’ kidney cells. Rats exposed to melamine alone (right panel) developed some of the dreaded melamine-cyanuric acid crystals (see red arrow). But rats given the antibiotic (left panel) showed no crystals.

In other experiments, the researchers mixed melamine with fecal samples taken from the rats. Cyanuric acid appeared after 24 hours, but didn’t show up at all in control mixtures without the fecal matter. Then, to narrow down what kind of bacteria might be responsible, the scientists performed a DNA analysis of the rat poop. They found seven species of Klebsiella, including one, called K. terrigena, which had been previously shown to convert melamine to cyanuric acid.

Finally, putting everything together, the researchers colonized the guts of rats with K. terrigena (by feeding a lot of it to them over four days). Kidney cells in these colonized rats were chock full of crystals, hemorrhaging and inflammation:

So, are gut microbes definitely the reason that the tainted milk made some kids sick? Not necessarily, Jia says, but it’s a strong possibility.

This type of bacteria is not a normal resident of the human gut. That might explain why the overwhelming majority of babies who were exposed to the tainted milk actually didn’t get sick.

So how would some of the kids (and pets) have picked up Klebsiella? Jia says that science can’t say for sure. But he notes that the babies who got sick tended to be from the countryside, rather than cities. “You could imagine that these kids, from relatively poor families, were exposed to a lot of dirt and soil, and may be more susceptible to having this type of bacteria,” he says.

Whether or not these gut microbes turn out to be the biological culprit in melamine poisoning, the data provide yet another example of the many ways that the bacteria that live on us, the so-called microbiome, can affect what we eat and how we live. The microbiome “can explain more and more problems that we were not able to explain in the past,” Jia says. “In the future, for toxicity and pharmacological studies, we need to redesign experiments to take this into consideration.”

In thinking about these possible microbial culprits, let’s not forget about the far more culpable human ones. In January of 2009, Chinese officials tried and sentenced 19 people who worked for the dairy manufacturers and knew about the melamine contamination: 15 went to jail for 2 to 15 years, 3 were imprisoned for life, and 1 received a suspended death sentence. In November of that year, two others were executed.

Just last month, meanwhile, grocery stores in Australia reported that baby formula is flying off their shelves, apparently because of a surge of demand from Chinese parents afraid to buy it in their own country.

*

Top photo by Jon Feinstein, Kowloon flyer by Cory Doctorow, both via Flickr

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital