When I think of prehistory’s greatest survivors – deep lineages marked by body plans that have remained consistent for millions of years – creatures like horseshoe crabs, velvet worms, and ginkgos immediately come to mind. Penis worms belong on that list, too.

Technically, and less hilariously, known as priapulids, these marine invertebrates have been burrowing into ocean sediments since the time the famous Burgess Shale was laid down 505 million years ago. The Cambrian form Ottoia prolifica roughly resembles modern priapulids (see the video below), and, as preserved gut contents show, this archaic penis worm was an opportunist that snarfed up just about anything it could extend its pharynx around.

Paleontologist Jean Vannier cataloged the gut contents of Ottoia in a PLoS One paper published last month. While about half the specimens Vannier investigated had empty guts, hundreds of Ottoia were preserved with their last meals intact. The fossils-within-fossils revealed a varied diet for the penis worm.

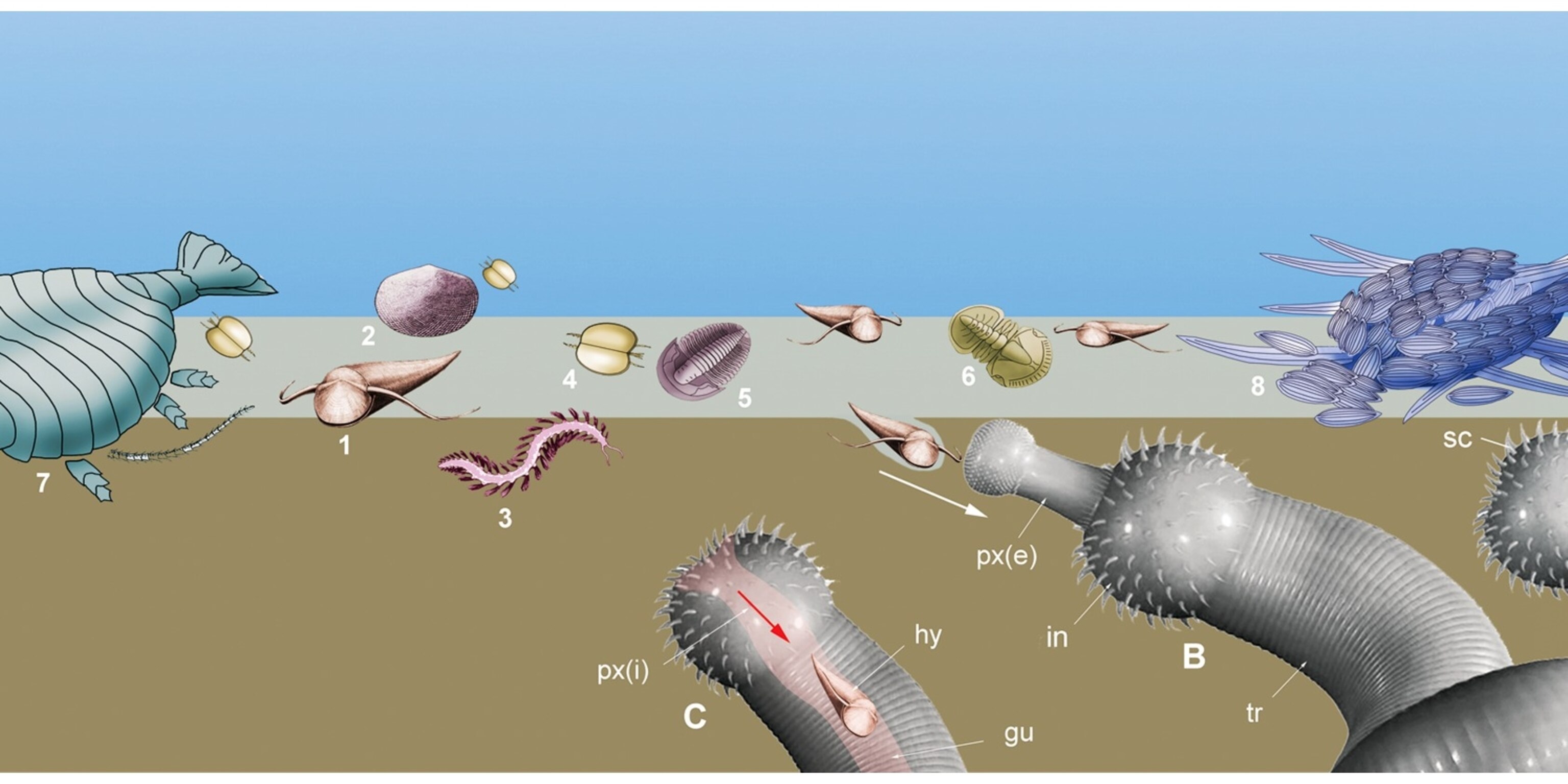

In general, Vannier found that Ottoia ate polychaete worms, bits of trilobites, shelled brachiopods, cone-shaped creatures called hyolithids, the armor of pincushion-like wiwaxiids, and parts of miscellaneous arthropods. And an exceptional fossil of several Ottoia arranged in “a wreath” around a large arthropod – Sidneyia inexpectans – hint that the penis worms weren’t above scavenging from larger prey when the opportunity arose.

Unfortunately, because of our geologic distance from Ottoia, we don’t really know how the tubular critter acquired such a wide range of prey. But Vannier suspects that the priapulid obtained nourishment in different ways.

Ottoia probably caught or accidentally ingested worms and small invertebrates as it sifted through seabed sediment, and occasionally scavenged large animal carcasses. The penis worm didn’t have a rigid, specialized dietary regimen. More likely, Vannier suggests, the omnivorous priapulid was a generalist and “facultative feeder”, able to take on whatever it could send down into its gut. In the Middle Cambrian seas, brimming with life, hungry priapulids didn’t have to be picky.

Reference:

Vannier, J. 2012. Gut Contents as Direct Indicators for Trophic Relationships in the Cambrian Marine Ecosystem. PLoS One. e52200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052200

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads