Edward Drinker Cope was not exactly known for his sunny disposition. One of the key players in the “Bone Wars” of the late 19th century, his long-running feud with fellow bone sharp Othniel Charles Marsh is the stuff of scientific legend. The two former friends tussled over everything from fossil sites to the naming rights of extinct creatures, with their embarrassing spat spilling into public view via The New York Herald in 1890.

Marsh was not the only source of regular discomfort and irritation Cope faced. In the early 1990s, photographer Louis Psihoyos and writer John Knoebber borrowed the naturalist’s bones for an extended — and unauthorized — road trip to meet some of Cope’s intellectual descendants. Along the way, they met with paleontologist Paul Sereno, who recognized that Cope had tooth abscess that undoubtedly made the cantankerous fossil hunter extra grumpy near the time of his death in 1897.

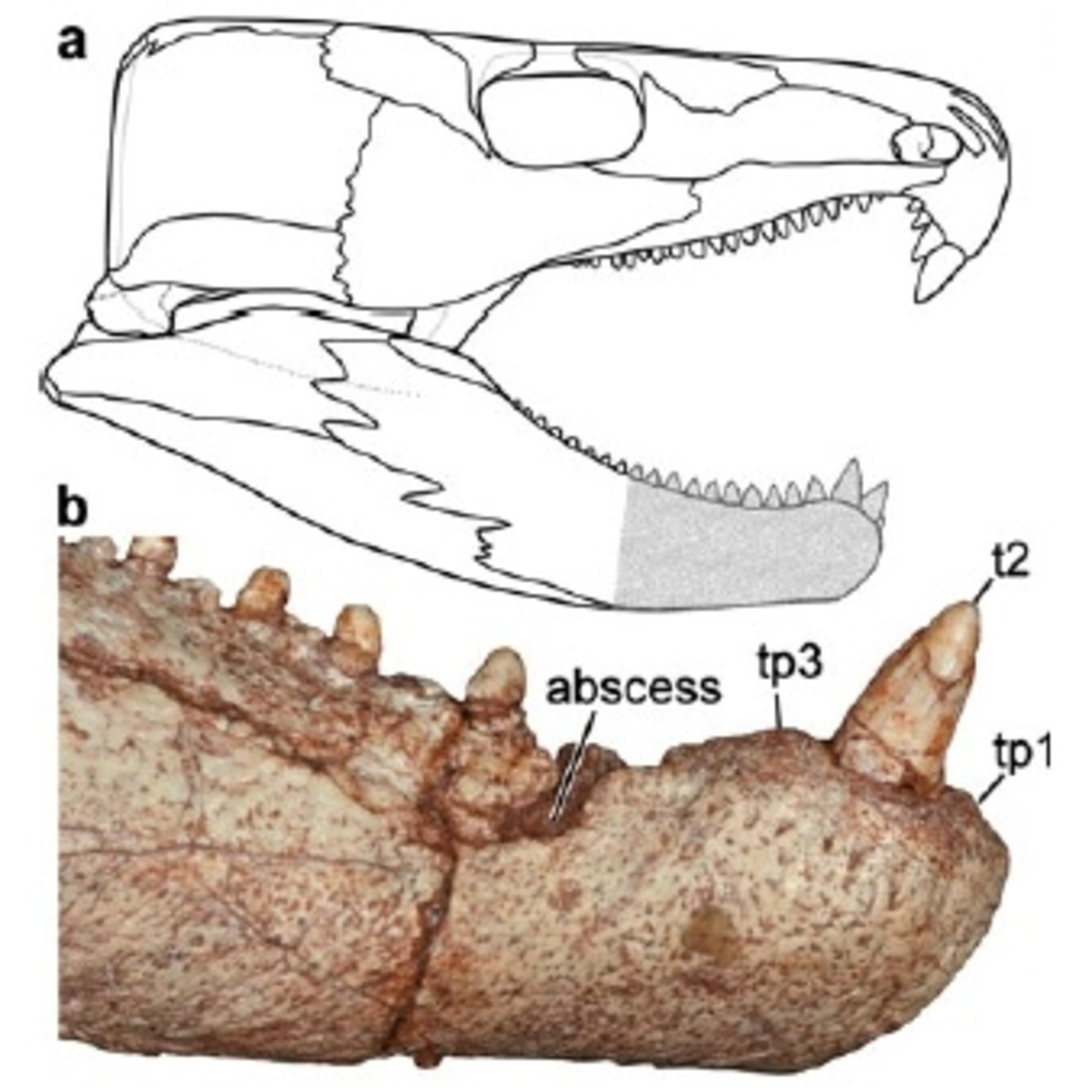

A specimen of one of the many prehistoric creatures Cope named during his career also suffered from a painful dental pathology. Found in the approximately 275 million-year-old rock of the midwestern United States, Labidosaurus belonged to an early radiation of lizard-like reptiles known as captorhinids, and Cope initially described it in 1896. Numerous specimens have been found since that time, but one — CMNH 76876 — shows the earliest evidence of bacterial infection yet discovered in a land-dwelling vertebrate.

The peculiar dental anatomy of Labidosaurus was at least partly to blame for its ailment. According to paleontologists Robert Reisz, Diane Scott, Bruce Pynn and Sean Modesto, a difference in tooth replacement may have made the reptile more susceptible to injury and disease. In other reptiles of the time, the teeth were only loosely fixed in the jaw and were constantly in the process of being replaced by newer teeth that erupted in the same sockets. Labidosaurus and other captorhinids, by contrast, not only had teeth that were more strongly fixed to the jaw, but new teeth erupted at a slower rate in different positions. If one of their teeth was broken, in other words, the area would be more susceptible to infection owing to the long and unusual pattern of replacement.

In the Labidosaurus specimen examined by Reisz and colleagues, the first and third teeth in the jaw were broken. The sockets had been filled in with bone. This was strange. In other reptiles, the broken teeth would have been lost and new ones would have taken their place, but in this Labidosaurus a pathology had developed instead. Three empty tooth sockets and a nearby abscess also showed signs of a deep infection, and the degree to which the pathology developed indicated that the animal had been living with the damage for some time.

We will never know exactly what happened, but the scientists behind the new study were able to reconstruct the sequence of events. The unfortunate Labidosaurus had lost the two teeth at the front of the jaw first, and oral bacteria had become trapped inside the jaw when the damaged tooth roots were covered by bone. Things only got worse from there. The bacteria triggered a severe bone infection, leading to the loss of three teeth and irreversible damage in the inflamed, pus-oozing portion of the jaw. If this chronic infection did not contribute to the death of the Labidosaurus, it was still active when the animal died.

Cope was not a particularly close relative of Labidosaurus — the ancestors and collateral relatives of mammals had already split from their common ancestor with reptiles long before 275 million years ago — but the injuries in the influential naturalist and the lizard-like reptile can be traced back to a similar condition. Though the anatomy of our own jaws is different than that of Labidosaurus, we only get two sets of teeth during our lifetime, and this gives injury and disease the opportunity to run rampant if we do not seek treatment. Cope could have blamed this bit of evolutionary inheritance from earlier mammals for his chronic tooth trouble, though his enmity towards Marsh alone left him feeling plenty sore.

Top image: A restoration of Labidosaurus by А. Кац. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

References: Reisz, R., Scott, D., Pynn, B., & Modesto, S. (2011). Osteomyelitis in a Paleozoic reptile: ancient evidence for bacterial infection and its evolutionary significance Naturwissenschaften DOI: 10.1007/s00114-011-0792-1

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads