Pakasuchus – the crocodile that’s trying to be a mammal

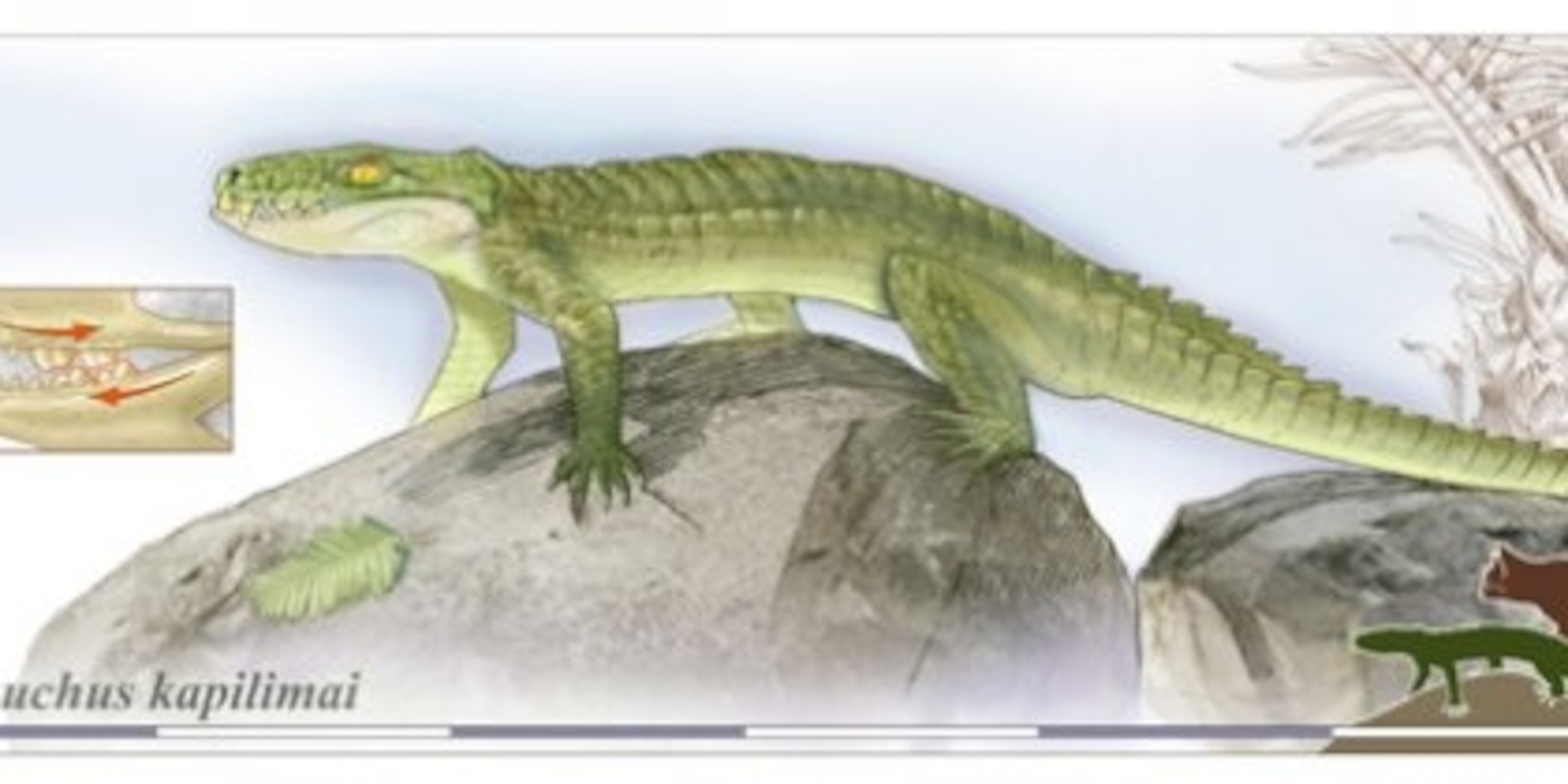

Around 105 million years ago, Tanzania was home to a very strange creature. It was about the size of a cat and had features that wouldn’t look out of place on a mammal – a slender frame, long legs, a short skull and a variety of teeth for cutting and grinding its food. But this was no mammal – it was a crocodile.

The newly discovered Pakasuchus has many trademark features that clearly mark it out as a crocodilian – the group that includes modern crocs and alligators. But it was very different to these living relatives, and some of its features were so mammal-like that its name even means “cat crocodile”.

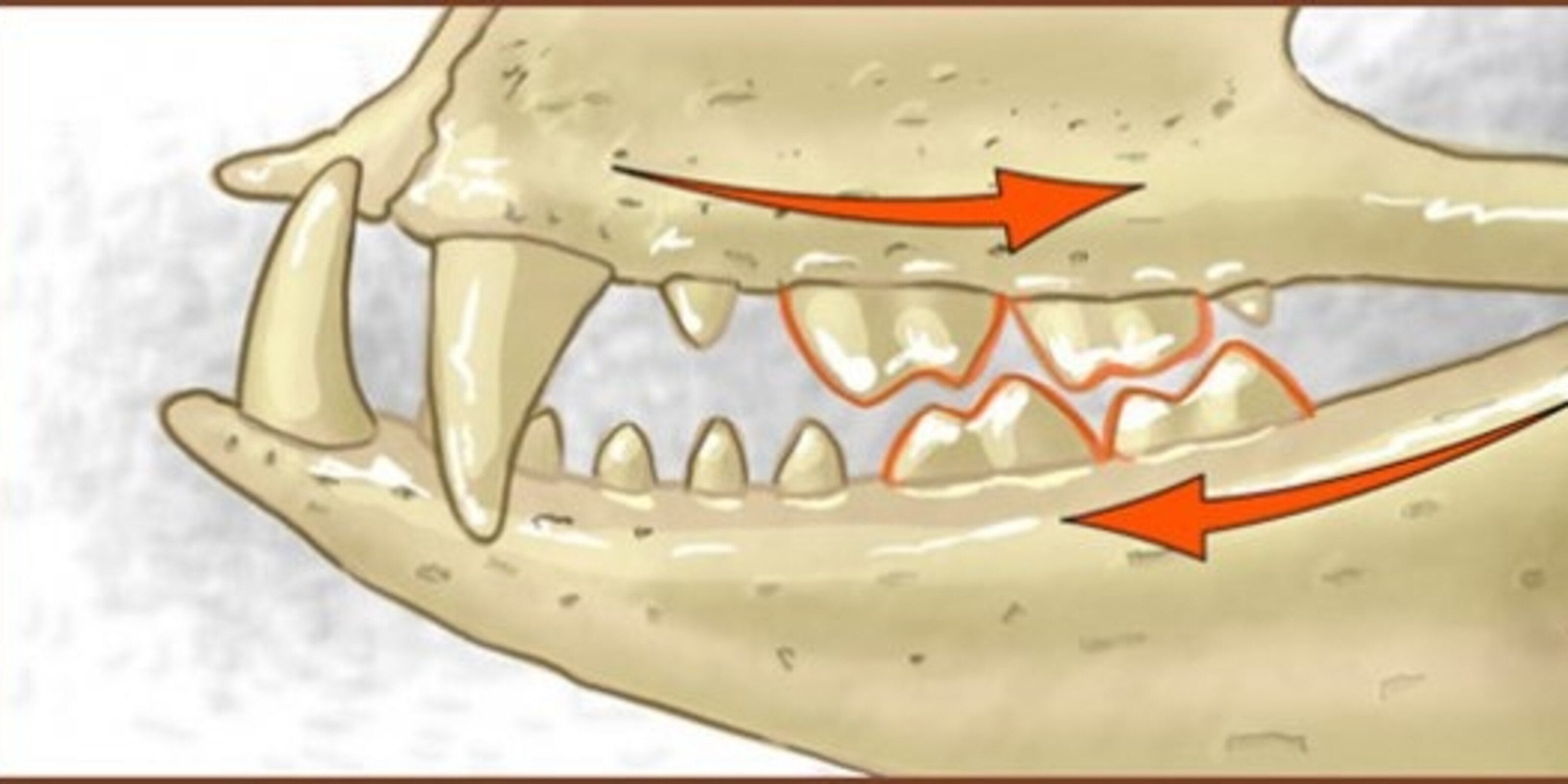

Consider its skull. All modern crocs have a snout full of consistently conical teeth. They snap at their prey with a powerful bite, before swallowing them whole. But Pakasuchus had a diverse set of chompers including piercing canines and grinding molars. It even had shearing teeth like those of cats and other meat-eating mammals. This ancient croc clearly ate its prey in a very different way. It’s dramatic proof that living crocodiles are just a thin branch of what was once an incredibly varied lineage, which came in many shapes, sizes and lifestyles.

Pakasuchus lived in the mid-Cretaceous period, when the gigantic supercontinent called Pangaea has begun to split up into separate land masses. In the Northern Hemisphere, small mammals were on the rise, exploiting all sorts of fresh ecological opportunities while dinosaurs loomed overhead. But in the Southern Hemisphere, small mammals were relatively rare and crocodiles came to fulfil the same roles using very similar adaptations.

Patrick O’Connor from Ohio University led a team that unearthed the little crocodile at Tanzania’s Rukwa Rift Basin. He named it Pakasuchus kapilimai after the Kiswahili word for ‘cat’, the Greek word for ‘crocodile’, and the late Professor Saidi Kapilima, who was an important part of the excavation. The team found several specimens of Pakasuchus but one in particular was in stunning condition.

The animal’s mouth was tightly shut when it died, so O’Connor used a medical scanner to study the details of its unusual jaws and teeth. The scans revealed that Pakasuchus only had 13 teeth, far fewer than its modern relatives. The teeth were very diverse, as the movie below show. And its molars fit together extremely well, and could grind and shear food with the aid of a mobile jaw. These traits are a standard part of a mammal’s hardware but they’re completely unprecedented in crocodiles.

Pakasuchus bizarre features don’t end in its mouth. It had long slender legs and nostrils on the front end of its snout, which suggests that it lived on land. Modern crocodiles, which primarily hunt in water, have short legs (they use their tails to swim) and their nostrils are on the top of their snout to allow them to breathe more easily at the surface.

Pakasuchus also lacks the heavy bony plates, or ‘osteoderms’, that are found on virtually all other crocs, whether living or extinct. Its tail is the only place that retains this body armour. O’Connor thinks that this species was an active hunter that sacrificed its cumbersome protection in favour of agility and speed.

By comparing Pakasuchus’s entire skeleton to those of several other crocodilians, O’Connor discovered that it belongs to a large extinct group called the notosuchians. This lineage is famed for its diversity. Pakasuchus was the only one with molars that met, but the others had their own weird adaptations. They included plant-eating Chimaerasuchus; Notosuchus with a possible pig-like snout and fleshy cheeks; Armadillosuchus with its banded, armadillo-like body armour; the bizarre, rabbit-toothed Yacarerani; and Anatosuchus with a broad, duck-like snout.

All of these species were medium-sized land-living creatures with features and habits that are decidedly unlike the typical crocodile. They were a highly successful part of the Cretaceous ecosystem, eking out lifestyles that mammals were sharing in the opposite hemisphere. Perhaps the eventual coming of mammalian competitors, or a significant environmental change, sealed the fate of these bizarre crocs. Whatever the case, it’s clear that today’s species are just the very tip of a once-diverse lineage.

Reference: Nature http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09061

More on crocodiles:

If the citation link isn’t working, read why here

//

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital

- Want to travel like a local? Sleep in a Mongolian yurt or an Amish farmhouseWant to travel like a local? Sleep in a Mongolian yurt or an Amish farmhouse

- Sharing culinary traditions in the orchard-filled highlands of JordanSharing culinary traditions in the orchard-filled highlands of Jordan